August

15

August

15

Tags

Why are we no longer in love with our Cities?

City Living Today

Cities and urban life are being increasingly discussed in the media, internet and society. These are topical disputes as to what our cities should look like, what experiences we should expect from them and who should be controlling this. This is of importance because where we live influences how we perceive ourselves and how we experience our lives.

We have evolving into an almost exclusively urban ape. For 99 % of the history of humans on earth, there were no cities. 1% of all urban-spaces are larger than 100,000 people but accommodate 63% of the world’s population. Others have suggested that we’re now at a point where over 80% of the global population live in cities . Paul Wheatley describes global civilization as moving into a third phase of urbanisation – where all cities will effectively merge into one:

It seems inevitable that by the end of the twenty-first century a universal city, Ecumenopolis, will have come to comprise a world-wide network of hierarchically ordered urban forms enclosing only such tracts of rural landscape as necessary for man’s survival.

With many studies pointing to a correlation between population size and city density, this trend is only likely to accelerate into the future . As this process of conurbation increases, many societal and cultural battles are starting to take place on this broader stage that includes the city itself – since this is where most of us live. City life was once so aspirational, what has changed?

“But for Western Europeans in the second half of the twentieth century, struggling to create a post-industrial urbanism… Dr Jekyll is losing control of Mr Hyde. Cities are seen as unpleasant, noisy, polluted and raw. We highlight the squalor, not the vibrancy, the discomfort not the liberation. These bleak images are smothering centuries-old visions of towns as civilised, sophisticated and gracious—everything we mean by ‘urbane’” Landry, et al.

Who is in charge?

The primary focus to be discussed here is how cities are engaged with in Western culture. Why are they such pinnacles of cultural status? Why do we have a love/hate relationship with cities?

Cities are very topical. For example, in London, at the same time that the Shard is gaining attention as its spire redefines the skyline; London’s previous architecture celebrity, Norman Foster’s London Gherkin, is up for sale. This is contributing to a more serious political discussion emerging as to what the nature of the London skyline should be, with “over 200 tall buildings, from 20 storeys to much greater heights, are currently consented or proposed. Many of them are hugely prominent and grossly insensitive to their immediate context and appearance on the skyline”. . What a city looks like both communicate and ‘constructs’ a lot about the social and cultural life of the people living there.

Across the Atlantic, there have been different conversations about city skylines, with the NY Port Authority claiming to own the NYC Skyline: telling a store to destroy its NYC Skyline-Themed plates. Ownership of a city skyline does appear strange, considering they are constantly changing. Skylines reflect the evolving character and needs of their populations. Across the US, there is an emerging discussion as to what the Millennials will want for their cities as they grow in economic influence. Studies suggest that they want to live differently, favouring variety and options, with good public transport.

“Generally, the size of rental and condo apartment units targeting people in their 20s and 30s is shrinking while the list of amenities tailored to them — electric-car charging stations, music studios, yoga studios, movie theaters and vegetable gardens — is growing.”

This raises questions as to who decides what a city should look like? Do cities grow organically or do they look exactly as planned? How do changes to cities reflect how we perceive ourselves and our communities? What does your city suggest to outsiders about you?

How do we feel about our cities?

What is interesting about cities is that most of us take them for granted; although we’re largely negative about them when prompted. I’ve discussed in other posts how the mood of post-modernity is to be fascinated by nature and rejecting of many aspects of our modernity project. Here our cities remind us of our ‘industrialized’ fears evoking how de-humanised we feel in a postmodern age. The power structures of city life appear to suppress individuality.

‘The deepest problems in modern life derive from the claim of the individual to preserve autonomy and individuality of his existence in the face of overwhelming social forces’ George Simmel

Robert Park, the urban sociologist, reflecting on the process of city-making stated:

“man’s most consistent and on the whole, his most successful attempt to remake the world he lives in more after his heart’s desire. But, if the city is the world which man created, it is the world in which he is henceforth condemned to live. Thus, indirectly, and without any clear sense of the nature of his task, in making the city man has remade himself’

From a cognitive metaphoric perspective, we think of cities as ‘containers’. They are urban islands seperated from the outside world. However, while there is consensus they are containers; rather than think of them as mixing-pots of vibrant cultural exchange, the common default is that they are cages. Think of advertising; we talk of the weekend ‘getaway’ or ‘escape’

The trouble with a cage metaphor is that you’re constantly trying to escape it. As Lily Tomlin observed,

“The trouble with the rat race is that even if you win, you‘re still a rat.”

If we have re-made ourselves as city dwellers as Park suggests, how is humanity different from before? There are three things to explore here:

- How do the origins of cities inform how we think about them today?

- Why do we identify so strongly with cities?

- What is the experience of cities that is causing such a disconnect?

Where did cities start? Why do we understand them as we currently do?

‘The concept of ‘city’ is notoriously hard to define’. Gordon Childe

How we relate to cities today is still very much influenced by how our ancestors first started to live in this way. Mythically and symbolically, the origins of cities can be found in our need to orientate ourselves to the universe. If we look at the early rituals and symbolism that guided a city’s development, it can inform how we see the role of cities today.

The first skylines were created by natural features on the landscape, in the form of trees or rocks. These created locus around which early societies could organise themselves. As Irwin (1990: 47, his emphasis) says

‘Throughout the whole ancient world the building of sacred monuments was first and foremost a rite by which man sought to identify himself with the source of the cosmic order’.

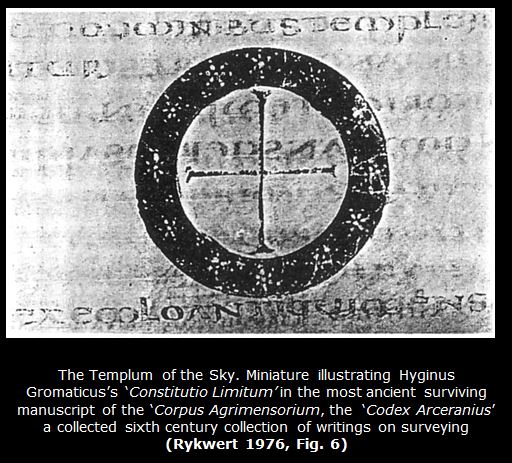

Semiotically, the first graphical representation of this was a simple cross: vertical tree on a horizon line. This evolved to be a cross under the sky – a cross in a circle. By the fourth and fifth centuries, we find this a popular symbol in use across the entire Roman Empire While there are obvious crucifixion symbolic considerations, the cross symbol was in broader use e.g. in Greek accounting at the time .

Another important symbolic association were the urban and geographical associations that are linked with the cross in a circle. This cross motif was used to orientate settlements and demarcate religious and secular boundaries. This was how all urban settlements were organised at this time and how surveyor’s guidelines were laid out as a process.

Rykwert describes the process:

It is a starry circle representing the sky which is quartered as the augur quartered his diagrammatic circle. … The purpose of drawing the diagram was to set the general order of the sky in a particular place, (1976: 47).

What is important here is that the earliest settlements and habitations were organised around us. The cross-in-circle symbolises our personal location in relation to the cosmos. This is a statement of personal orientation when we are within these structures. Think of a legend on a map or a compass that we hold – these are designed around this symbolic frame.

This was not just a Roman tradition. A hieroglyph from Egypt called nywt ![]() (Budge 1971: 34) that means ‘village, town, city’. Rykwert (1976: 192) illustrates this character nywt as a vertical cross

(Budge 1971: 34) that means ‘village, town, city’. Rykwert (1976: 192) illustrates this character nywt as a vertical cross ![]() ; he suggests that the cross-in-circle connoted a city in the Roman empire. This shouldn’t be a surprise considering that the Roman Empire created the two greatest cities of Rome and Constantinople and this symbol is associated with both.

; he suggests that the cross-in-circle connoted a city in the Roman empire. This shouldn’t be a surprise considering that the Roman Empire created the two greatest cities of Rome and Constantinople and this symbol is associated with both.

The origins of the word urban can be found in this symbolism. The word urbs was derived from urvum ‘ the curve of a ploughshare’ or urvo ‘I plough around’, and orbis ‘ a curved thing’ ‘a globe’ ‘the world’. ‘The word for city immediately provoked the association with ploughing’ (Rykwert 1976: 134). This should not be a surprise since the first cities were agricultural centres.

Christ has often been connected to ploughing symbolism in early Christian art (Milburn 1988: 1-7)from parables in Mathew 13 and Luke 8. Connected to this are the accounts of the founding of Rome and Constantinople whose boundaries and layout are both described by John the Lydian as being cut into the earth by oxen yoked to a plough (Burch 1927: 129).

Christianity built the first two great urban cities. However, Saint Augustine suggests a third, that there are two holy cities, Rome which symbolizes all that is worldly, and Jerusalem (the city of heaven)

Jerusalem was believed to be at the spiritual centre-of-the-cosmos, as much as in the secular world ‘all roads lead to Rome’. Constantinople was established as the second Rome; it was Constantine’s city for the eastern empire and the first to adopt the cross-in-circle as a symbol

Over history, it has been a decreasing trend to name cities after their founder. Rome was named after its fratricidal wolf-weaned King Romulus; Constantinople, after the first Christian Roman emperor Constantine; Caesarea was named for Caesar; Washington DC for George Washington; Stalingrad for Stalin. We now live in an era that is less interested in historical narratives; hence, the origins of cities are less important today. We are more likely to personify the collective shared character of cities.

Other ways we perceive cities as people

If the founders above are based in history, other origins are non-secular.There was an older tradition for many cities to be named after guardian deities; perhaps the most famous is that Athens was named after Athena.

Greek gods such as Hermes were frequently associated with market places in many cities, but many other Greek Polis (city states) adopted individual Gods. This could be very literal; the Palladium was a statue of Athena Pallas which was also known as ‘The Luck of Troy’. This was believed to have protected in turn, Troy, Rome and Constantinople over periods of time. The Palladium was moved from Rome to Constantinople by Constantine in a political move that indicates the primacy of his new Roman capital. The protection of this statue was thought to explain the fall of Rome while Constantinople thrived.

To some extent, the Vatican’s association with St Peter, when compared to Venice adopting St Mark as its patron saint, can be seen through this lens. Later Britannia was used by the British Empire as a personified spirit that was borrowed from Roman times.

This mythological dimension has been explored more creatively by Warren Ellis, who founded a new type of superhero called ‘Jack Hawksmore’ – the God of Cities. Much of Ellis’s writing reflects sociocultural and trans-humanist themes. It does address an interesting gap in modern mythology.

Historical founders, spirits, religious personages and deities all created a rich heritage for us to think about cities as living people from when they were first constructed.

Our Personification & Identification with Cities

While we don’t think of cities being under the protection of a deity anymore, that doesn’t mean we don’t think of them as living beings. These conventions of deities primed us to think of them as responsive entities. From a semiotic perspective, we use a lot of anthropomorphic metaphors to discuss cities. We talk of the heart of Europe, transportation arteries, head of state, the fitness of the economy, crime as sickness, certain cities turn their nose up at others, the city that never sleeps, etc. We perceive cities as organic and living beings that we are part of.

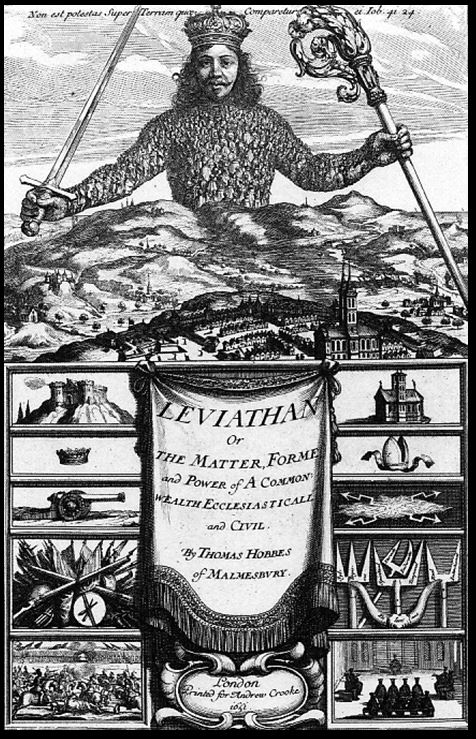

This is not a new association; the Old Testament often uses the body as a metaphor for the city, such as Jezebel being a metaphor for the corrupt city Babylon. There are many modern examples of somatic symbolism in literature. One of the more famous visual examples, is the cover of Thomas Hobbes’ 1651 Leviathan –where society is literally depicted as one body.

We still talk about the head-of-state as a shortcut to the body politic? These themes of the interchangeability of us and our cities has been explored in modern art, such as that by Dan Mountford or Alpha-Tone .

We also find the reverse of this with architecture expressing more anthropomorphic themes. ‘The Dancing House’ or ‘Fred and Ginger’, by architect Vlado Milunić in co-operation with Frank Gehry, Prague, Czech Republic almost defies reality to create the impression of two dancers.

This is also a consistent theme of the metaphoric work of Nigel Coates the architect

Perhaps the most tragic and traumatic societal illustration of this metaphor was the September 11 destruction of the Twin Towers. George Lakoff, a cognitive linguist, in defining ‘Metaphors of Terror’ describes the attack as:

‘The devastation that hit those towers that morning hit me. Buildings are metaphorically people. We see features—eyes, nose, and mouth—in their windows. I now realize that the image of the plane going into South Tower was for me an image of a bullet going through someone’s head, the flame pouring from the other side blood spurting out. It was an assassination. The tower falling was a body falling. The bodies falling were me, relatives, friends. Strangers who had smiled as they had passed me on the street screamed as they fell past me. The image afterward was hell: ash, smoke, and steam rising, the building skeleton, darkness, suffering, death’.

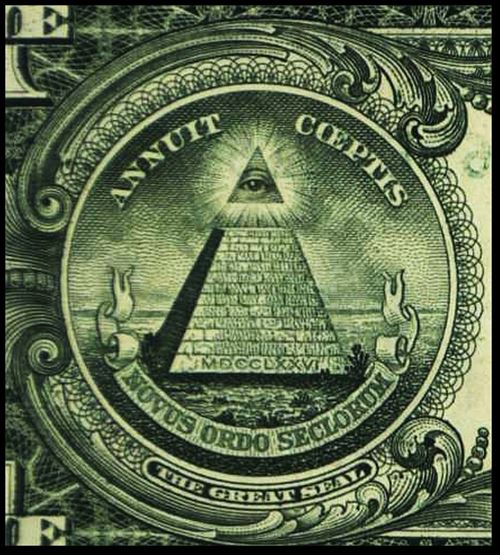

More widely, this metaphor of buildings as people should be familiar to most Americans, with an anthropomorphic representation of buildings on their Dollar Bill. This is the reverse of the great seal, which illustrates the ‘Eye of Provenance’. A building that is anthropomorphized with an eye.

Recalling that in architecture, the central mandorla or central round window on Churches such as at Notre Dame, Paris have been likened to being the ‘Eye of God’.

“The eyes of the Lord are on the righteous.” (Psalms 34:15)

More broadly, this might explain the trend for Ferris Wheels to be found in most larger cities. The most famous examples are called ‘eyes’. This is more than just that they offer views, it’s also that they look like eyes on the personified city skyline.

A more negative role of this symbolism are the Eyes of T.J. Eckleburg, in ‘The Great Gatsby’.

These are thought to symbolise the loss of spiritual values in American? and the growing commercialism. “But his eyes, dimmed a little by many paintless days, under sun and rain, brood on over the solemn dumping ground.”

Destruction and cities.

Our identification with cities as a metaphor of a shared body is so strong, that the loss of cities has profound impacts on how we think about our communities and personal identity. Historically, the destruction of Delft in 1654 had a significant impact on 17th C Europe

‘On Monday, 12 October, 1654, shortly after half past eleven in the morning, one of Delft’s gunpowder stores exploded and destroyed a large part of the city. This painting by Van der Poel shows the terrible damage caused by the explosion’.

This explosive power had not been experienced before this time. The significance of the paintings is that cityscapes were a relatively rare form of painting at the time. These paintings helped draw attention to skylines as an art form.

If we look at the second world war, it was the tactics of ‘carpet bombing’ urban centres that left an indelible scar on the face of Europe. The brutal and deliberate targeting of urban centres by both sides of the war are detailed by Anthony Beevor is disturbing detail.

Hollywood and Popular Culture appear obsessed with destroying our major cities; it takes little effort to find movies that all result in the destruction of the city. In this case, NYC as the world’s Modern Capital, is often the target. Why do we want to see our cities destroyed as entertainment?

One of the reasons that the idea of cities and buildings be destroyed resonates because of its drawing upon older symbolism. If we look at Tarot Cards, this meaning is encapsulated in the tower card

Tarot cards are useful reductions of archetypal psychological imagery. If we look at the imagery, what we see are two people thrown from a tower that is being struck by lightning. In main effect? is for the crown of the tower to be knocked down. This scene has different interpretations but most agree that the people had crowned it king, suggesting it was the ultimate authority. Also, that by living in the tower they were cut off from other people (being in an ivory tower). The lightning strike returns them to the ground but does not harm them. Finally, the lighting has different interpretations from an act of God to something more symbolic; Carl Jung suggests that lightning represents ‘a sudden, unexpected, and overpowering change of psychic condition’.

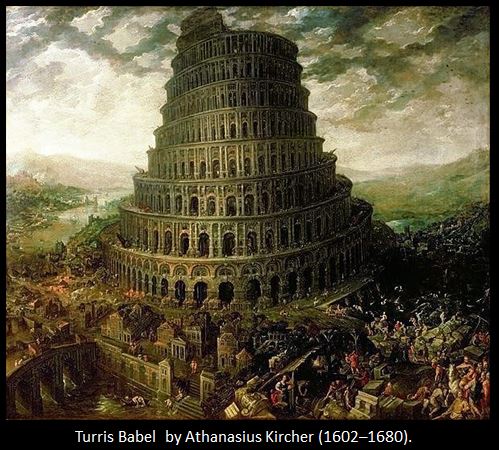

As a story, this scene evokes the building of the Tower of Babel of ancient Mesopotamia. Here King Nimrod erected a tower so tall that he would be able to enter directly into heaven. This was struck down by God, and caused the multiplicity of language as a punishment. Also, simultaneously creating work for generations of semioticians, linguists and people working in cultural fields.

And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth. And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.

So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

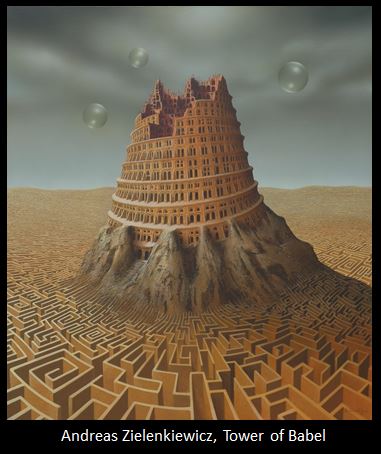

Images of the Tower of Babel have many permutations. All appear to represent the first ‘Skyscraper’- a building that scraped the heavens; close enough for God to smite it down.

This was the inspiration of the Fredersen’s headquarters in the 1927 movie Metropolis; the central tower is believed to be based on the Tower of Babel.

More modern versions of the Tower introduce new themes.

Interestingly, Andreas Zielenkiewicz work, starts to introduce the Labyrinth that I discussed in my last post . The fallen tower, without a crown, resulting in a literal maze for those left still standing. The confusion of communication.

A striking image I referenced here in this post, The Map of Andrea Ghisi’s Laberinto, illustrates this journey to the centre and elevation. Here the central figure tries to navigate out of a maze to an elevated place. Pillars and towers are often symbolic of raised consciousness. This scene also evokes the process by which landscapes were ‘surveyed’ by both religious and secular authorities, discussed above through the imagery of the cross and circle.

Part of our morbid fascination with seeing cities being destroyed appears to be a bit of cultural self-loathing. I’ve discussed before how the postmodern era is characterised with a fetish for the pre-modern age. Many of the Hollywood stories take away modernity by some supernatural or ‘act of god’. We appear fascinated to see what will happen if we were forced to reboot how we live.

It’s informative that many of these dystopian films end with the pairing of man and a woman, usually alone. Ending the story with a modern day ‘Adam and Eve’ to start humanity again. This same symbolism is present in the ‘Tower Card’; a man and woman that are ejected from the Tarot Card, tumbling to the ground, to start again wiser than before.

The underbelly of the city

Zielenkiewicz’s use of the maze is interesting in the context of building a city. In the Bible it never used the term ‘Tower of Babel’, it suggests that Babel is the city. One of the aspects of the Labyrinth is that it is often used as a metaphor for the underworld. There is a connection between these conceptions of the labyrinth, the darker part of the subconscious, with the underworld as Hell. This can be manifested to the shadow of where we live.

‘In Les Miserable, by Victor Hugo, this underworld to the city is described: as ‘a dark, twisted polyp, […] a dragon’s jaws breathing hell over men’. …. The labyrinth, in accordance with the theriomorphic isotropy of negative images, tends to come alive, in the form, say, of a dragon or ‘a fifteen-foot long centipede’. The ingesting, a living sewer, is linked to the image of the mythical, devouring Dragon….Babylon’s digestive apparatus’.

This symbolic connection of Hell, the Great serpent and the Labyrinth was also perceived by Eugene Ionesco as representing the opposite of Paradise. If goodness is order, evil must be disorder. The straight path or the maze. This is also reflected in the way that Dante’s Hell is described as being a labyrinth. Italo Calvino, talks to this aspect of cities:

The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.

Looking semiotically at advertising today, I was able to show that we express a lot of the negativity of modern city life as a maze – evoking the hell aspects of this symbolism. It also presents the city as a cage to be escaped. This sense of the underbelly of the city being ‘hell’ has been explored in countless Hollywood films http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/starring-the-subway, something that is well celebrated.

Perhaps a film that unites many of these elements was Mimic. An overview of the plot unites many of the themes discussed here: To fight a disease, we genetically tamper with cockroaches that kill the illness. However, the genie is out of the bottle, and these bugs continue to evolve; to the point where they live in the under city, coming above surface only to hunt humans for food. Again suggesting conclusions about modern humanity: that it doesn’t understand the implications of the science it uses.

Skylines as the Face(s) of a City

If we can easily define the underbelly of a city, what does the skyline mean? In starting this discussion, many of the disputes about cities are about how they look. Why do we care what they look like?

“looking at cities can give a special pleasure, however commonplace the sight may be,”

The aesthetic considerations of skylines are an important aspect to their nature. It’s not just the size of a skyline but their complexity that speaks to a comparable measure of civilization. The complexity of skylines does appear to contribute to their appeal.

The aesthetics are subjective and do create different emotions

“People can point out specific visual features or attributes in an environment that create pleasant feelings and distinguish those features from other environmental attributes that evoke negative emotions”

From a purely utilitarian perspective, we use skylines to navigate our way around cities. Although, this perspective is isovist , in that we can only see the visible space from a certain space, not the entire skyline at once (sentence doesn’t seem finished). This is why it’s really easy to get lost in a foreign city. It’s an important definition because it also illustrates that skylines change with new buildings, dominating and obscuring others, and why this is such a hot topic. The space between buildings creates a sense of density of a city.

By seeing a skyline this ‘tends to lead to the idea that a skyline conveys information about the ‘whole’ city. If we are an integral part of our cities, doesn’t the skyline say something about us an individuals?

The Skyline as the ultimate cultural status symbol

Earlier I alluded to the city life being a ‘rat race’, this is not just within the city city-against-city. Increasingly, as the economic playing field is being leveled across global economies, this is becoming important. There is a constant jockeying between the old and new world to have the most desirable cities. There are many annual lists that rank the great cities of the world or here

‘Then again, we do compare cities: it’s is part of social life, a form of life. We compare cities, frequently, typically, and in many ways. The comparison of cities remains a popular activity’. Alan Blum

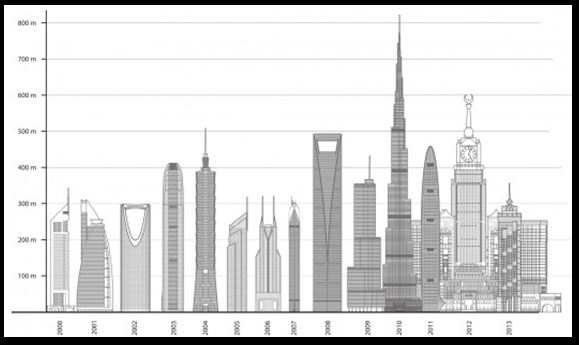

It is believed that there is, to some extent, a competitive city-race occurring on the global stage

The competitor cities of New York, Frankfurt and Tokyo loomed large as the detailed London plan articulated the potential for supporting strategic elements of London’s economy. And the dynamism of Asia’s urban skylines arguably stretched London’s horizons upward as the previous Mayor responded to the sense of a fading urban image by changing planning regulations to allow tall buildings … the geopolitics of huge buildings is just one of the ways in which China is announcing its global ascendance

We compare cities because we are urban apes; status-performance is a central driver of our personal and social behavior.

“A skyline is the chief symbol of an urban collective. It testifies that a group of people share a place and time, as well as operate in close proximity and with a good deal of inter-dependence,” (Attoe, 1981, p. 1).

For nearly 80 years, the skyscraper was largely an American-only phenomenon and seemed to symbolize the energy, enthusiasm and optimism that characterized the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The desire to measure up in a Freudian competition is seeing a rise in the tallest buildings being dominated by Asia in 2013. Asia now represents 45% of the 100 tallest buildings

A key consideration here is that we inherit cites as much as we contribute to their future growth. As much as the current generation grows the city, we move around a city, which in part was designed for our ancestors.

At the same time, there are places where competing narratives of a people – their history, values and identities – are being fought out in the very fabric of the city itself. There are many people in modern democracies who do not recognise themselves or their pasts in their nations’ capitals, sometimes despite the strenuous efforts of city planners and political leaders to represent the nation in this way

When we consider the anthropology of a city, it is something that is collectively created rather than being the product of one mind or physicality

Thus the city does not exist in an individual’s mind or ‘out there’ as an objective physical landscape but as a collective entity that gathers people’s emotions and memories, mixes them with architecture and elicits distinctive practices and ways of being.

Is part of our negativity about cities the sense that we are not part of the collective voice that defines a city?

Can we engage more? What is the best way to interact with a city?

Michel de Certeau discussed in detail how to ‘read’ a city. From a semiotic perspective he talks of the city as being an ‘immense texturology that ‘lies before one’s eyes’. He contrasts the pedestrian vision of a city against the almost godlike ‘eye’ view from being on a skyscraper. He challenges us in the way that we relate to a city by positing that walking is a postmodern means of resisting the large city power structures. In walking a path of your own choosing, you are making your own reading of the city.

We can’t escape from some aspects of the skyline though. Some features dominate in a way that we cannot exclude them from our vision. The polarising effect of the Eiffel Tower on Parisians is well documented, perhaps most amusingly by Roland Barthes talking of Maupassant

‘Maupassant often lunched at the restaurant in the tower, though he didn’t care much for the food: It’s the only place in Paris, he used to say, where I don’t have to see it’.

The danger in this discussion is that, like people we know, we don’t always notice the smaller changes: ‘“landscapes are like the books which we constantly look at but rarely read”

What is a city?

‘What is the city? How did it come into existence? What processes does it

further; what functions does it perform; what purposes does it fulfil?’

Andrew Irving identifies a multiplicity of city types:

It is a foundational diversity that is responsible for bringing the many different types of city into being; the discursive city, the mythical city, the physical city, the poetic city, the underground city, the late-night city, the working city, the women’s city and the men’s city. To this list we might also add Low’s categories … the ethnic city, divided city, gendered city, contested city, de-industrialised city, modernist city, postmodern city, fortress city, sacred city and traditional city

If we think through these metaphors of cities, it’s clear that cities can unite around a shared narrative amongst its denizens.

Cities need a story or cultural narrative about themselves to both anchor and drive identity as well as to galvanise citizens. These stories allow individuals to submerge themselves into a bigger, more lofty endeavour. A city which describes itself as the ‘city of churches’ fosters different behaviour patterns in citizens than a city that projects itself as a ‘city of second chances’.

Although, when we talk of a shared narrative, perhaps Roland Bathes was correct in seeing this more as an active discourse

The city is a discourse and this discourse is truly a language: the city speaks to its inhabitants; we speak our city, the city where we are, simply by living in it. (Barthes,1967:168)

In discussing urban reinvention and the future of cities, Charles Landry suggests

Urban reinvention is not only about physical change and creating new economic sectors, it is in essence a cultural project as you have to bring the population with you and engage them in your renewal story…

Living in a Modern City

“All the world’s a stage” William Shakespeare.

From a perspective, while there is a shared discourse within a city, it has also been suggested that cities can be experienced in terms of either reading or being experienced. One way of looking at the experiential aspects is as a performance; where the environment is a stage set with props, and individuals use this setting to engage with the wider social audience. This was a frame for the city that Lewis Mumford described as ‘a theater of social action’.

Many urban theorist have been positive on? the role of ‘cultural economies’ or ‘experience economies’ in the future development of cities and their communities

‘All cities need to gain recognition and to get onto the global radar screen in order to increase their wealth creation prospects and to harness their potential. Creativity, the cultural distinctiveness of place, the arts and a vibrant creative economy are seen as resources and assets in this process… The best cultural policies combine a focus on enlightenment, empowerment, entertainment and creating economic impact.’

Richard Florida has published many works discussing the role of the Creative Class and its impact on city development and demographics. If we personify cities, there is also a need to think of the cultural ecology of a city. As Paul Makeham states

In a broader sense the physical spaces, architecture and design of cities comprise myriad performative qualities including tension, irony, intertextuality and self-reflexivity; as Edmund Bacon observes, one of the ‘prime purposes of architecture is to heighten the drama of living’. Indeed, cities as a whole can be understood as sites upon which an urban(e) citizenry, in the ‘practice of everyday life’, performs its collective memory, imagination and aspiration, performing its sense of self both to itself and beyond.

We can see this in emerging art forms focusing on urban connectivity and ecology, as has been conceptualised and explored by contemporary artists like the UK based artist Stanza

End of the Street

The biggest shift in cities, aside from their size and sophistication, has been from being? historical or religious to being ‘corporate’ skylines. There was a corresponding focus of the role of cities, from being a ‘fortress’ and place of refuge in war, to being a modern city that owes its existence to the market place it grew up around.

While the discussion above has discussed the collectivising nature of cities in forming a common identity, Gunter Gassner correctly warns that ‘in our contemporary society without a meta-narrative, without one ideology and one religion we can agree on, the idea of representational city-images is doomed from the very start’.

The 21st century will be a search for meaning, as many have noted. In a primordial sense meaning is transmitted through stories that tell us who we are and where we are going. Charles Landry

This has left David Harvey to ask

‘the astonishing pace and scale of urbanization over the last hundred years means, for example, that we have been remade several times over without knowing why or how. Has this dramatic urbanization contributed to human well-being? Has it made us into better people, or left us dangling in a world of anomie and alienation, anger and frustration? Have we become mere monads tossed around in an urban sea?

If we think of how we refer to tall buildings as ‘skyscrapers’ that dominate the landscape, this evokes the imagery of the Tower of Babel. The related myth to that of the Tower of Babylon is the Story of Icarus flying too close to the sun. In both, the protagonists are burned by seeking knowledge that is restricted. Even Prometheus tells a similar tale of punishment for seeking divine knowledge.

As our cities continue to rise to the sky, how does this sit with the current pervasive themes of anti-modernity? Perhaps this is the challenge to town planners and architects. Perhaps a consideration as we move towards a Ecumenopolis – a planetary city – is what metaphor we want our cities to evoke. Cities defined by the skyscrapers evoke status competition and allegories of Babel.

Architect Bjarke Ingels is designing a revolutionary new zoo – Zootopia – for Denmark. His vision is

“You’re seeing more and more that the distinction between the city and nature … is blurring more and more,” he says. “It becomes more relevant to make sure that the other life forms can actually cohabit successfully with us…I really do think that if you can make great zoos, where so many different species can live in close proximity and harmony, you really can make great cities,” he says.

Sounds like a great vision for some tired rats in a maze.

wow. really in depth piece! Love that nyc video

Thanks for reading and commenting

I guess like many things in life there is a dichotomy of views about cities. Having just spent some years in European cities (as a tourist not a resident) those older and more character imaged cities endure and the wonderful architecture, cultural representation, preservation of past multiple generational periods are a delight. But also evident is the disadvantage for residents of ‘rat race’ living, travel inconvenience, high prices of property and the inevitability of the same retail chain name incursion in every high street. I also find as I age the convenience of career and facilities offered by cities fades as I seek a quieter ‘retired’ lifestyle.

Demand for city life is evidenced by continued high residential and office/retail rentals. This may belie your contention that we are not in love with our cities. It’s merely that we step onto the escalator of life – some of us get off at one end to allow newcomers to step on.

There is however one main feature changing the face of modern cities. Population explosion has created city elements most undesirable. The London and Paris riots reflect dissatisfaction for those not enamoured with city pressures and the very distinct ‘have and have not’ divide. This also makes crime management a major city issue.

We will continue the love hate relationship with never ending cities – whatever culture we are we need cities even if we have had them for only 1% of our human existence.

Great article and an interesting challenge to thought processes – many thanks

I agree with your observation that cities continue to grow. I suppose the broader challenge is to realise that some of the ‘glamour’ or ‘magic’ that used to be part of the ‘going to the big smoke’ myth has been eroded by the realities of living in them. I’m not saying that people don’t like cities. You can be on the escalator of life and not be in love with the journey. However, the metaphor your use is one where you are giving power of your movement and direction over to the city…like a mouse in a wheel.

Of course a question moving forward is that we continue to build more complex digital cities – Facebook and Twitter can be viewed as digital cities, with thriving transnational communities – do we need to live on top of each other? Part of the reason driving conurbation is the increasing need of budgets to centralise services from a diminishing tax base. This is where ideas of ‘living cities’ became more in vogue.

Pingback: Emerging Metaphors for the Human Body | :: Culture Decanted ::

Hello mate greeat blog post