July

31

July

31

Tags

The Psychology of the Maze as a Modern Symbol

Why are we still a-maze-d by labyrinths?

With a diverse range of permutations, the Maze is a symbol that has been with humanity since the pre-historic era. So pervasive is the labyrinth within human symbolic communication, it is impossible to think of a human era where it was not a deep structural metaphor that has guided human thought.

Why talk about Labyrinths? My response is a semiotic one; there appears to be a juxtaposition of the meaning behind the symbolism that is being expressed across postmodern culture. I’m interested in how the meaning of this symbol is changing and why? The labyrinth and maze appear to be experiencing a resurgent popularity; it’s interesting to explore what is driving this engagement.

A modern renaissance of the Labyrinth?

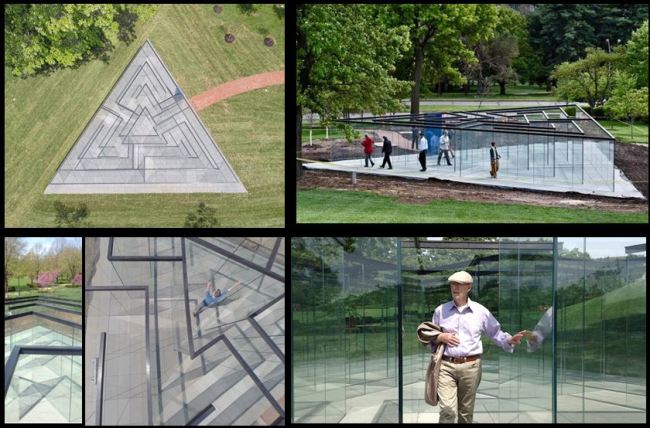

Only a couple of months ago, Robert Morris unveiled his new triangular labyrinth. A very postmodern take on the Labyrinth where the confusion is amplified by the transparency of the design rather than obscured by high walls.

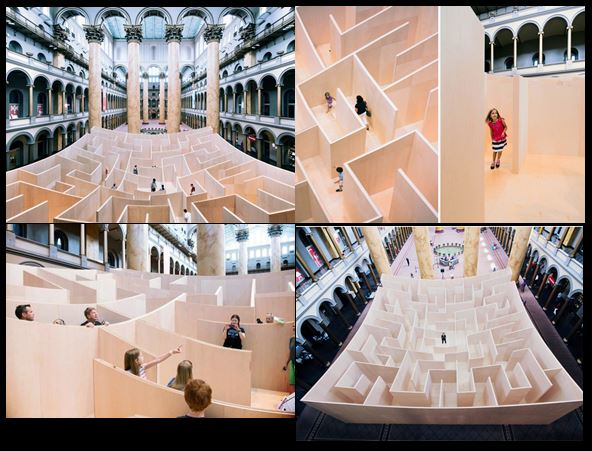

More recently, the opening of the ‘National Building Museum in Washington D.C.’ ‘Big Maze’

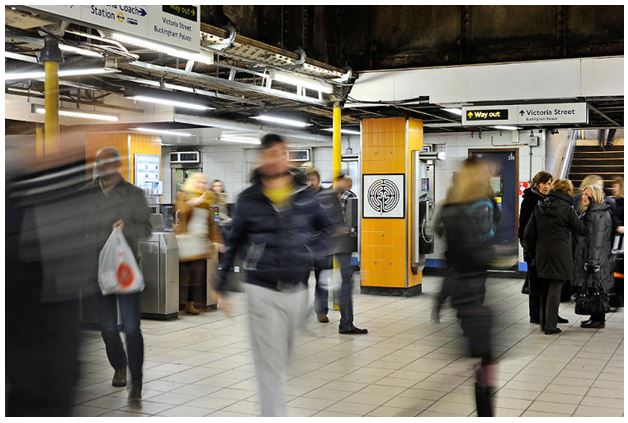

In 2013, Mark Wallinger celebrated the London Underground’s 150th Anniversary by placing a labyrinth in each of London’s 270 Tube stations: ‘A reminder that no matter how busy the Tube may get, there’s always a way out’.

In 2010, Franco Maria Ricci, the publisher behind Luigi Serafini’s Codex Seraphinianus, created a seven-hectare maze at Fontanellato – the world’s largest maze.

More broadly, in the USA it has been suggested that there has been a wider upsurge in interest in labyrinths, with more than 1000 labyrinths having been built in meditation garden settings, at retreat centres, churches, hospitals and prisons in 2011.

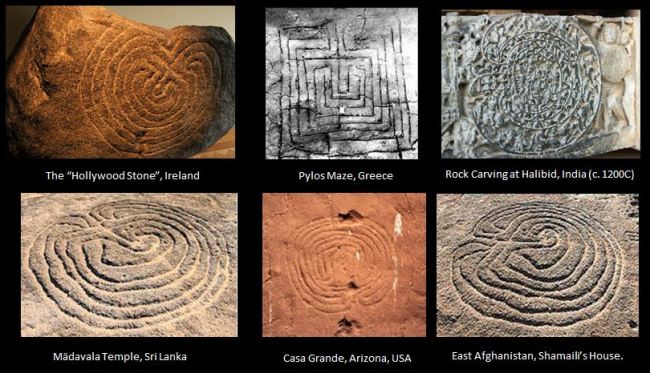

How old is the Labyrinth Symbol?

The Labyrinth is one of the oldest symbols of humanity, probably dating back to 2500BCE and most likely even older. It’s also a motif that we find across many cultures and continents. As a symbol that evokes Carl Jung’s ‘collective unconscious’ as we find the same symbol speaking to similar meaning, across different discontiguous cultures and unrelated time periods.

Why is this symbol still popular?

To answer why this symbol is still popular, we need to recognise that we need to disambiguate the meaning between a Labyrinth and Maze. The two words are often used interchangeably in conversation. And it is here that there is the most interesting aspect of discussing the symbolism of the Labyrinth today.

A maze is not a synonym of a Labyrinth, in many ways it’s an antonym

A Labyrinth is an apparently random and convoluted party that is unicursal in nature. A maze is an intricate network of paths which is multicursal and usually designed as a puzzle.

Modernity appears to have lost something of what they symbolise of the labyrinth. It is this feature of what the maze vs labyrinth means in our modern western culture that is interesting to explore. In order to understand what has changed, it’s important to quickly review the changing meaning of the symbol from its first appearance.

The two words for similar looking symbols mean very different things. From an etymological perspective, the word Maze is believed to come from a Scandinavian word for a state of bewilderment or confusion . This is where our word ‘amazing’ comes from. Whereas the etymology of Labyrinth likely originated from the ancient greek word labrys, a double-headed axe used by the Minoans on the island of Crete. Thus, labyrinthos may mean “house of the double-headed axe.” (the Minoan connection will be discussed more below).

The Maze/Labyrinth is one of the most resonant archetypal symbols of humanity and found across most cultures from different starting points. At its most simple, it could be explained by the simplicity of its pattern. To draw a simple one, all you need to do is weave a vermicular route, repeatedly from a centre, and you can create a rudimentary Labyrinth. A artistic comparison would be a ‘marigold’ pattern created in different cultures which use protractors or compasses in art; or pyramids from anyone that notes the form of sand dropped into a mound.

However, this rational explanation of illustration doesn’t explain the consistency of symbolism that is associated with the motif across different cultures.

“[across the] world been associated with all aspects of human life. It has been used as a symbol of fertility and birth, as well as one of purgatory and death. It has religious and meditative importance in Hindu, Christian, Islamic, Buddhist and Shamanic rituals [Conty 2002]”

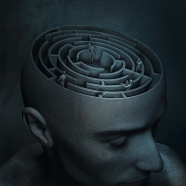

It is possible that its symbolic strength comes from being analogous for our own mind’s structure

The complicated structure of the labyrinth also mimics the biological structures of the human brain, and so another possibility for the endurance of this myth is our unconscious recognition of this building’s elaborate construction and its remarkable similarity to our own anatomy.

However, before discussing the use of the symbolism of this motif, it’s worth discussing a different possible origin of the symbol itself. This is a consideration that is often overlooked in discussions, largely due to the influence of the Cretan Labyrinth and the Minotaur. In culture, the inspiration of the creation of a symbol is not necessarily the same as it signification at a later time.

Dancing Instructions or identity map?

If you cannot get rid of the family skeleton, you may as well make it dance.

George Bernard Shaw

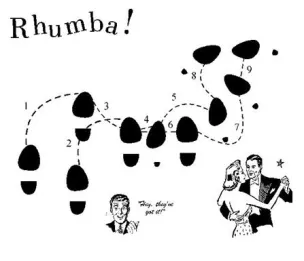

What are these patterns depicting? If we are encourages to walk them, they are guided paths. Paths that we routinely step though are related to terpsichorean rituals: to dance. Dancing is something that has transcended the secular and religious in many early cultures

‘in its more primitive sense, a religious act or ceremony by the aid of which men co-operate with the gods for their own advantage or for the mutual of both…In short, a pantomime or imitation of these magical processes is engaged in the by the dancers and this is regarded by them as either as a strong hint to the gods to take the necessary magical action to ensure rain or growth, or as assisting them in the process…It does not explain the rite or give any reason to it, it narrates and describes it only’ (Spence 1979:2).

At this time the belief-systems often had a different conception of the cosmos and of death from today. There was no heaven and hell, there was this life and an afterlife. It was believed that there were supernatural doorways between these ‘realms’. Mythical trees such as the Norse World Tree were such portals – these are axis mundi (world pillar). Associated to this, there are a range of animals called psychopomps which had the ability to cross this threshold; usually animals associated with carrion such as crows, raven, wolves, etc. Since Shamans often talk of crossing over to the otherworld to gain wisdom and knowledge, it’s not surprising then that we find early Shamanism rich with dancing and music rites (Ellis Davidson 1976). . The rites to get to the other world often involved intoxicants, dancing and music. This connection back to the axis-mundi can be seen in Siberian traditions, where the wooden-frames of their drums that create the music are claimed to have come from the world tree (Hatto 1970).

This symbolism continued, recalling that in later Christian Traditions, in a popular account, Christ is crucified on the branch of the Tree of Life at the centre of the universe in Jerusalem. The ‘Dream of the Rood‘ which was recorded on the Anglo-Saxon 8th C Ruthwell Cross. This was very similar to Odin being hung from Yggdrasil the world tree, as well in a more shamanistic story. Here we see the primacy of a central pillar and the afterlife to the universe being very influential on symbolic thought.

Many terpsichorean rituals involve symbolic dancing moves that speak to memorized patterns. Learned by rote, these patterns would be recorded as routes or trails – a map.

‘Mazes would naturally be associated with the initiated, and they would be trodden or danced through; both initiation and treading, dancing or riding are, as we have seen, regularly associated with mazes’ C & W Russell (1991).

The implication of this is that if you learn a pattern in this life, when you pass to the otherworld, as scary and unknown that it is on the otherside, you can repeat the dance to find your way to your kin. Mazes functioned as a primordial supernatural GPS. If you know the maze in advance, you defuse the only real threat on the way to the centre, disorientation.

This connection to the otherworld can be found in other cultures as well.

This is where it gets difficult to work out what comes first, the chicken or the egg, or in this case: the dance or the depicted steps? Later in time, it’s clear that the symbol was guiding the way that they were walked or danced. In pilgrimages in Christian traditions ‘walked the Labyrinth’.

Steps on pilgrimages used penitent crosses, which functions as meditation stations. It is likely that early Christian labyrinths symbolised mental and physical ‘maps’ or contemplation.

The designs evolved as well, with a tradition of octagonal labyrinths differing from the traditional labyrinth.

It has been suggested that these unique octagonal shapes reflect the baptismal fonts that were in the churches. These were eight-sided to symbolise Christ’s resurrection on the eighth day. (for why this is the 8th day and not the 3rd is discussed in depth here ).

Additionally, there have been connections made between Labyrinth dances and the Renaissance era dances . It’s not a focus here, but the rich traditions of Garden Mazes and architecture that use labyrinths as the foundations for their designs. While the discussion above revolves around dancing, equestrian jumping mazes also fit into this discussion

Types of Labyrinths

More technically, Umberto Eco has identified three types of labyrinths:

- The Linear Labyrinth– a continuous line that wraps around itself. He identifies the nature of a unicursal maze: ‘the thread of Ariadne which the legend presents as the means (alien to the labyrinth) of extricating oneself from the labyrinth whereas in fact all it is the labyrinth itself’.

- The Mannerist Labyrinth – multiple paths, some dead ends that engage the traveller with choices. This is often tree-like and there is usually one right path.

- The Network Labyrinth – ‘a network is a tree plus an infinite number of corridors that connect its nodes. The tree may become (multidimensionality) a polygon, a system of interconnected polygons, an immense megahedron’.

The linear, is a traditional Greek labyrinth; the Mannerist is closer to what would colloquially be called a maze; and the network has more modern implications, which shall be discussed below.

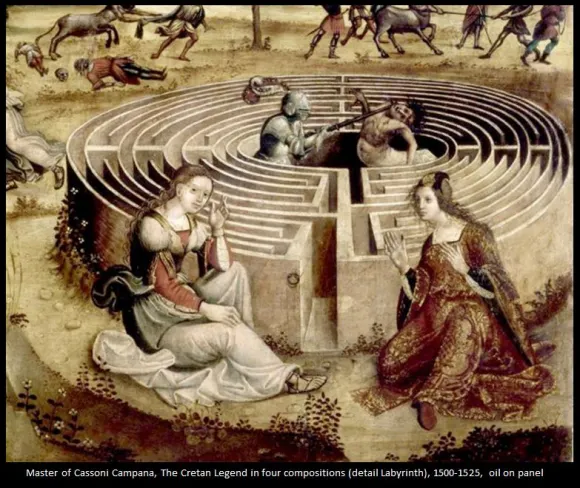

The Mythic Story: The Labyrinth of the Minotaur

A lot of the western symbolism about the labyrinth derives from the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. There isn’t scope within the current discussion to explore every aspect of this mythography. There are many points of departure that are ripe with meaning in this story.

Cropping the story, Crete’s Queen gave birth to a monster called Minotaur. Minos, the king of Crete, commissioned Daedalus to create a structure to contain the Minotaur. At the time, Crete from its position of regional strength, demanded tribute from other nations like Athens (to feed the monster). Theseus, a Prince of Athens, was amongst the tribute. Ariadne fell for the prince and helps him to navigate the labyrinth with a golden thread and kill the Minotaur.

In versions of this story, ancient Labyrinth all have a centrality; they are unicursal with a way in and a way out. Those that look to this Greek tradition have a monster at the centre.

‘The Cretan labyrinth-design…has no blind alleys. Every part of the figure has meaning, and even when a path is apparently going in the wrong direction, it leads to the centre’

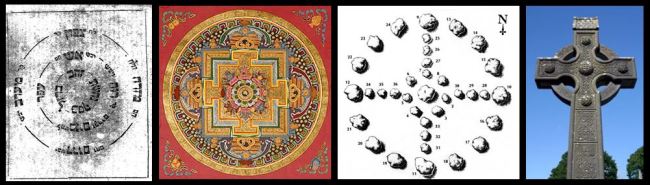

With this focus on the centre, this evokes another type of archetypal symbol. It’s informative to think here of a Jungian psychological understanding of figures that have centres. Figures that conform to this symbolism are called Mandorlas. Again, this symbolism is found across every culture: Hebrew, Tibetan, American Indian, Celtic Irish, it is global in its expression.

The Mandorla or Kylkhor means ‘centre-surround’ in Tibetan. It is a symbol of transformation which encompasses the totality of an individual’s reality around a central axis.

‘Carl Jung recognised the mandala as a universal image of wholeness and a fundamental image of the self that appears in most cultures in many different forms. He became increasingly interested in the appearance as expressions of wholeness.’

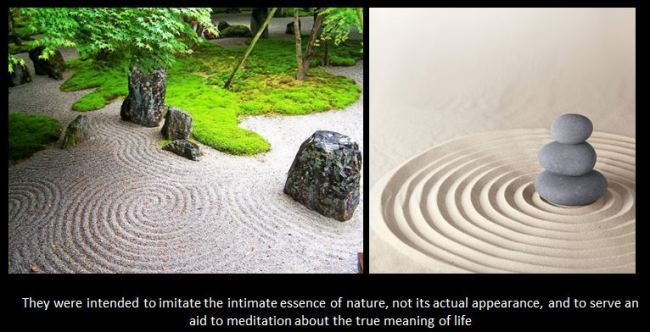

The reflective nature of this thinking is something that can be found in Zen Gardens in Japan

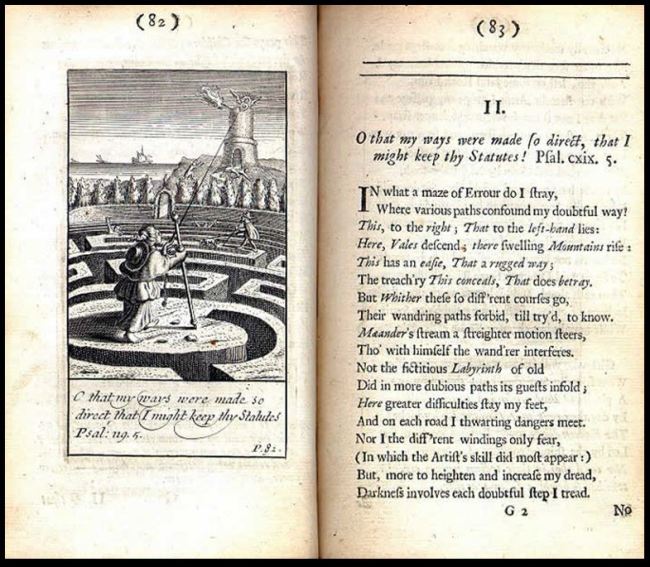

The Map of Andrea Ghisi’s Laberinto, illustrates this journey to the centre and elevation. Here the central figure tries to navigate out of a maze to an elevated place. Pillars are often symbolic of raised consciousness.

The journey of the labyrinth is analogous to our own journey, in the process of self-individualisation through our lives

‘One of the oldest images of the mystery of life, death, transformation and return is the labyrinth (the individuation path is also like a labyrinthine spiral) in which we fear to loose ourself. …The labyrinth is one of our oldest of symbols; it depicts the way to the unknown centre, the mystery of death and rebirth, the risk of the search, the danger of losing the way, the quest, the finding and ability to return’

Marie Von Franz explained this connection of the labyrinth in relation to our subconscious

“The maze of strange passages, chambers, and unlocked exits in the cellar recalls the old Egyptian representation of the underworld, which is a well-known symbol of the unconscious with its abilities. It also shows how one is “open” to other influences in one’s unconscious shadow side and how uncanny and alien elements can break in.”

The Minotaur from the Underworld

It is in this unconscious shadow aspect that we meet the Minotaur. Although, Umberto Eco makes a strangely entertaining suggestion that there has to be a Minotaur in his ‘Linear Labyrinth’

‘there has to be a Minotaur, just to make the experience interesting, seeing that the pathway through it (setting aside the initial disorientation of Theseus, who doesn’t know where it will lead) always leads to where it has to lead and can’t lead anywhere else’.

However, this does significantly downplay the psychological and mythical importance of the Minotaur. Daedalus created the Labyrinth to hide the Minotaur from society. This is our repressed, dark and even evil side.

As for what this monster connotes, the Minotaur is most commonly viewed as a symbol of destruction. When Theseus slays the Minotaur, he metaphorically kills death, and so the monster represents evil personified, a dark and terrible beast. According to myth, the labyrinth was built to hide the Minotaur, this aberration of nature, to hide the scandalous evidence of its birth.

The similarities between the labyrinth and Dante’s Hell, with its concentric rings guarded by Lucifer at the centre, are abundantly clear. The two figures are often depicted as beasts; here the Minotaur getting the torso of a man.

If we look to Dante we can see this in the way he talks

“Midway in the journey of our life I found myself in a dark wood, for the straightway was lost. Ah, how hard it is to tell what that wood was, wild, rugged, harsh; the very thought of it renews the fear! It is so bitter that death is hardly more so. But, to treat of the good that I found in it, I will tell of the other things I saw there./ I cannot rightly say how I entered it, I was so full of sleep at the moment I left the true way;…”

This theme was recently explored in the movie Inception. The story involves various dream states; one of the characters is Ariadne or the architect (the same named heroine that gives Theseus the Golden Thread to escape the Labyrinth).

In more Jungian terms Ariadne is the main character’s anima; as much as Beatrice was for Dante in navigating the 9 Circles of Hell. From a Jungian perspective the anima, is a contrasexual archetype of a male’s psyche (the female equivalent is an animus). Engaging with the anima, is an important part of the individuation journey, opening men up to emotionality, creativity and relationships. In stories, we find that women often appear to men to help them through the labyrinth, these women are anima.

Robert Graves in discussing the nature of heroes journeys and stories suggested that all heroes journeys to the otherworld or Hell are really labyrinth myths. It is a convention that many mythical heroes go to the otherworld (representative of their subconscious) in order become ‘heroes’. This is the role of Ariande to Theseus as she helps him overcome his ‘minotaur’.

There is a connection between these conceptions of the labyrinth, with the darker part of the subconscious, with the underworld as Hell. This can be manifest to the shadow of where we live.

‘In Les Miserable, by Victor Hugo, this underworld to the city is described: as ‘a dark, twisted polyp, […] a dragon’s jaws breathing hell over men’. …. The labyrinth, in accordance with the theriomorphic isotropy of negative images, tends to come alive, in the form, say, of a dragon or ‘a fifteen-foot long centipede’. The ingesting, a living sewer, is linked to the image of the mythical, devouring Dragon….Babylon’s digestive apparatus’.

This symbolic connection of Hell, the Great serpent and the Labyrinth was also perceived by Eugene Ionesco as representing the opposite of Paradise. If goodness is order, evil must be disorder. The straight path or the maze.

‘Here’s a maze trod indeed, through forth-rights and meanders’

The Tempest, Shakespeare

The Labyrinth’s Life Line: The Thread

“Labyrinths have many meanings. Two of them stand out: the fear of getting lost and the pleasure and challenge of exploration. These opposing meanings, not uncommon in symbols, explain partially our fascination with them”.

Having explored some of the psychological and mythical dimensions to the symbol, it is informative to expand this discussion to the Labyrinth as a journey. As something we might walk.

There is a big difference between the labyrinth and the maze, which was discussed above. However, they both involve the willingness to get lost upon entering. However, Penelope Doob points out that one rewards persistence, and the other, memory and intelligence. One forces you through a set journey, the other deliberately seeks to confuse and frustrate.

The way that Theseus is able to navigate his journey was through Ariadne’s gift of the Golden Thread. Interestingly, the meaning of the word ‘thread’ is from the old English ‘to cause to twist or turn’.

Gilbert Durand believes that the thread and labyrinth together are a ritual conveying the idea of difficulty and the danger of death in seeking our destinies. It is a testament to the maxim; high-tech problems need low-tech solutions. Here a simple thread acts as a way of defusing a complex maze.

Morrison in writing about the metaphoric role of the thread states:

‘This thread acts as an agent of inscription, of writing one’s way through the maze. Keeping track of the choices one has made in the past, the decisions and pathways travelled, allows one to be located in the present‘

This aspect of the thread being a temporal marker might start to suggest what the modern attitudes to the labyrinth are. Coming from a different perspective, Alan Dix in discussing cyberspace states (my emphasis):

The potential dynamics of a system are inherently branched and non-linear. Scenarios are important because our experience however branched and complex within space, is always linear through time. We live a single thread of life, not a multiplicity of potential paths. This is why it is easier to browse a simple history list for a hypertext than a more complex representation. Mazes are synonymous with complexity, but strangely enough early mazes were essentially linear: they had one spiral or convoluted path.

What is the Modern perception of the Labyrinth Today?

Perhaps a consideration here is on how the straight thread vs the disrupted thread corresponds with the way we think today. In discussing the Greek way of thinking, Bruno Latour has suggested that the Greeks thought in terms of straight threads and deviations as being different modes of thinking. One represented the continuation of history, the other perhaps more disruptive.

- The straight path was of reason and scientific knowledge.

- The clever and crooked path was that of technical knowledge.

He believes that the myth of Daedalus is that all things deviate from a straight line.

Within a more postmodern frame of thinking, we need to consider what a labyrinth suggests to us today. Broadly, postmodernism is driven by our interest in self-transformation through culture, language, aesthetics, narratives, symbolic modes and literary expressions and meanings. However, it is also defined by being fragmented, discontinuities, pluralities, chaos, instabilities, constant changes, fluidities and paradoxes that define the human condition. In some ways, the straight-thread is modernism: continuities, progressions, stable and ordered. There are concrete objectification and part of larger continuous narratives. Postmodernism represents a disruption to this journey.

Psychologically, if the labyrinth journey of old was a journey to a centrality. This is analogous to our journey within to individualisation or self-actualisation. Symbolically, in this journey we seek to confront the shadow parts of our ‘self’ represented by the Minotaur. Walking or contemplating a labyrinth, in gardens, art or stories is a way of evoking this experience. When considering the re-engagement with this symbol, could it be that in a postmodern world we seeing this as an increasing need here? Compton suggests that our lives are not working; we are troubled or want to feel our way to a dilemma is when we engage with the labyrinth. Asking is ‘The thread running through this is the desire humans have to be whole and no longer fragmented’. Is the increasing appeal of the labyrinth a subconscious desire for us to have a better sense of our centre in a fragmented world where the constant drive to individuate leaves some with a feeling of ‘standing on nothing’.

Speaking of the labyrinth as an archetype in a (post)modern world, Morrison beleives:

‘Even if we dismiss labyrinths as irrelevant, child’s play, or just smart design, the idea of the labyrinth remains incredibly relevant to the world of the mind, our interiority. The labyrinth serves as a useful metaphor for reading, writing, creating, thinking, perceiving, and for life itself. Psychologically, the labyrinth is an archetype that still moves us and describes life for us in some essential way’.

The Labyrinth in Popular Culture.

This discussion has focused on the origins, psychology, symbolism and the ways that the labyrinth/maze dichotomy has changed over time. How do we engage with the labyrinth today? To explore this it’s informative to look at how we are using it in popular culture. This could be across many different expressions of culture; so I’ve chosen two types of storytelling, one long and one very short. I’m going to use Movies and Advertising to explore this theme. Although, this analysis could have been just as interesting looking at literature through the works of Borges or Umberto Eco’s ‘Name of the Rose’ – they just tend to be less visual.

Eventually everything connects – people, ideas, objects. The quality of the connections is the key to quality per se.

Charles Eames

Labyrinths in Films

From a mythic level, the Greek myth of the Labyrinth and monster is still very much in vogue. Most successfully, it’s the mythic foundations of ‘The Hunger Games’, where young people are offered as tribute for the entertainment and needs of the monster (the state). They have to fight in an arena (labyrinth) to escape.

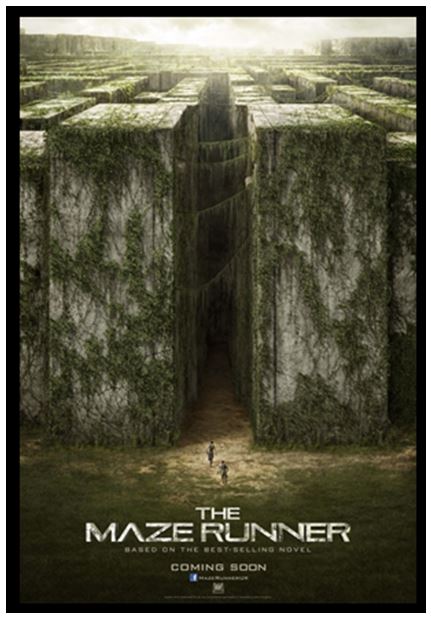

Very similar to this is the soon to be released “The Maze Runner”, where young people with no memories have to form teams in a maze to escape.

Several big budget films over recent years have used a plot of heroes being challenged by a constructed maze. In Aliens vs Predator predators create an automatic maze to allow them to hunt the ultimate prey in the arctic. Resident Evil uses the layout of Racoon City as a labyrinth. Here the underground city is controlled by a sociopathic Artificial-Intelligence called Alice and the survivors are hunted through the maze by a genetically engineered monster. Harry Potter portrayed a less grim use of the maze, although it still resulted in the death of a central character.

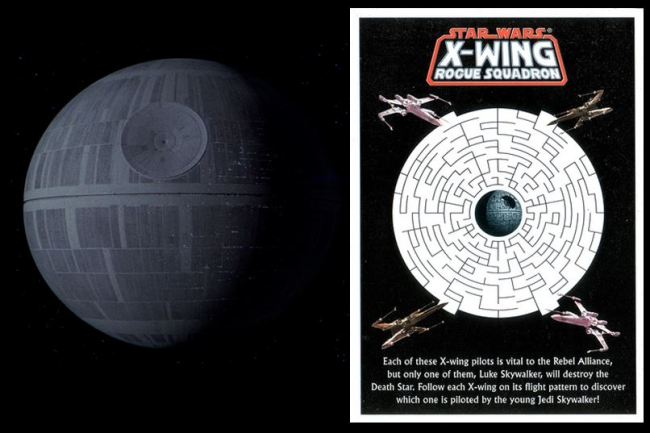

The labyrinth has also been a central theme to Star Wars, where Luke and Han enter the Death Star ‘Maze’, find their anima in ‘Leia’, battle the monster in ‘Darth Vadar’ and leave triumphant. It is this part of the narrative that marks a more self-confident and independent Luke Skywalker emerging.

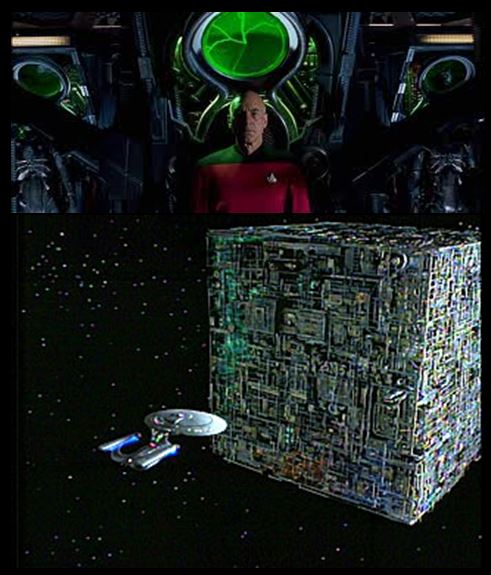

The Star Trek take on this theme was a clever inversion though the Borg Cube. While the Borg (a hostile cybernetic race) live within a maze, if you enter this maze you don’t find yourself, you lose your sense of identity to the collective. The Borg assimilates and shares a collective-intelligence though their collective; this hive mind coalesces through the Borg Queen. The reverse of an anima role, she takes identity by force rather than guiding you to self-actualisation.

This darker aspect of the Maze has been used in horror movies over time. The horror film Saw shows the ‘Jigsaw Killer’ create elaborate mazes and challenges to ‘educate’ the abductees of their true natures. Brutally violent, the franchise takes the challenge of the labyrinth to the next level. It does present an interesting take on a unicursal labyrinth though, since the route is always the same. The choices presented are not different directions but different solutions through life-threatening puzzles.

The film that helped pioneer the technological and modern maze was the 1997 Canadian film Cube, where different ‘participants’ are moved like rats through a maze across different challenges.

These films also start to introduce the dimension warping potential of a maze. There has been a strong influence on the virtual nature of mazes by Escher. Douglas Hofstadter’s ‘Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid’ explores the ‘strange loop’ of self-referencing objects and their logical contradictions.

Josh Whedon’s ‘The Cabin in the Woods’ successfully plays with themes of the mythical Minotaur, ‘strange loop’ mazes and modernity. Again, we see a group of young people within a maze, fighting for survival.

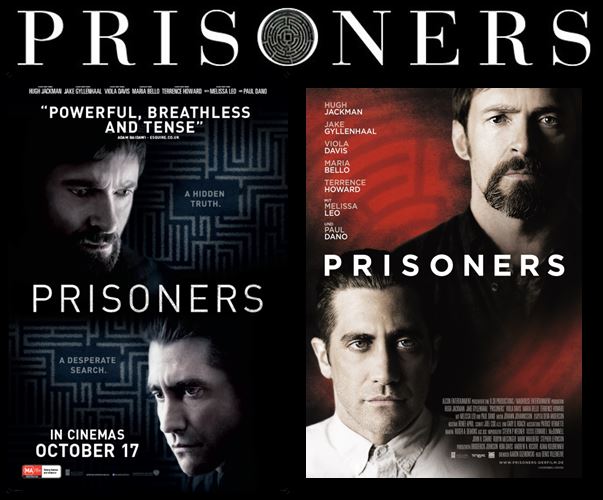

Last year Prisoners (2013) was released with mazes at the centre of the story line. Interestingly with the lead Detective named Loki (Viking God of magic and illusion related to the meaning of maze in Scandinavian); speaking to themes of hidden truths and the need to seek answers at the centre of the mystery. The storyline revolves around abducted young girls, alluding back to the anima conception discussed above from a Jungian perspective.

The more intense thriller/horror film that uses the labyrinth as a central theme is “The Shining”, where the journey is metaphorically to his inner Minotaur as his sanity unravels.

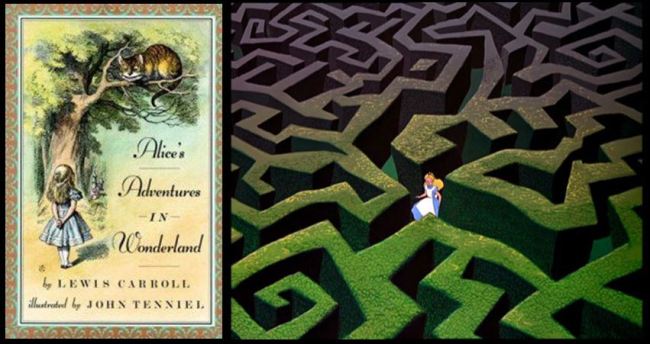

A different and more mythical telling of a young girl’s journey and growth was Guillermo Del Toro’s 2006 Pan’s Labyrinth. A complicated tale that merges reality with the mythical, it tells the story of Ophelia’s rebirth through the labyrinth.

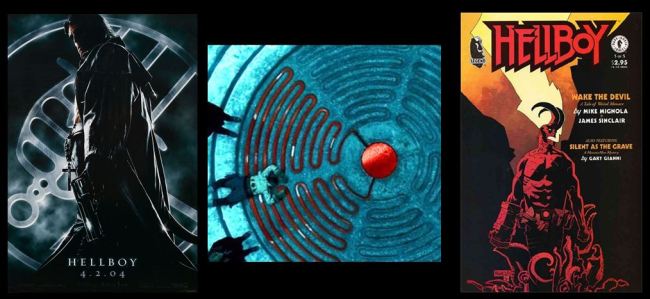

Interestingly, in Guillermo Del Toro’s other movie ‘HellBoy’, the labyrinth is used to bring back to life the source of Evil, Rasputin. A blood sacrifice by Rasputin’s acolytes starts the magic to pull him back from the realm of hell. Here the Minotaur, Hellboy, is a ‘good’ horned demon who is literally the key to the labyrinth (the door to Hell).

Labyrinths as Games

Many of the films above evoke the experience of the labyrinth as a game. This might be a game with mortal consequences but the idea is that the ‘the winner survives’. This is most likely a natural evolution of garden mazes as a form of experiential entertainment. This grew in popularity in the 16th and 17th centuries. There are many famous examples from Villa d’Este, Tivoli, Italy to the Imperial Gardens, Peking, China.

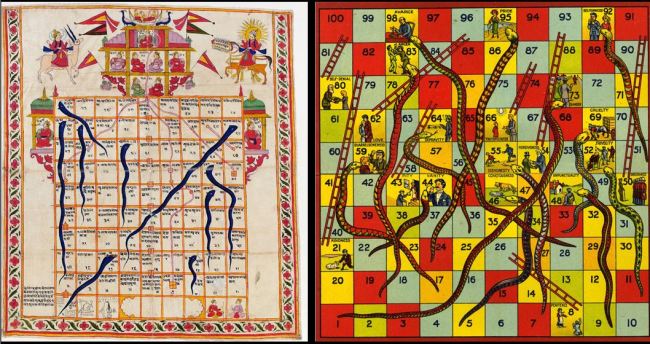

At its most simple, ‘snakes and ladders’ is a maze based game where the decision making, within the maze, has been put into the hands of the roll of the die. Originating in India, this has remained a popular board game in western cultures.

It’s not surprise that many of the most successful early videogames are labyrinth and maze based – all with their own Minotaur’s. This theme of knowing/learning the right path is a central part of the current generation of games. Perhaps a topic for another post, the role of labyrinths in video games has been discussed in depth by Steffen Walz.

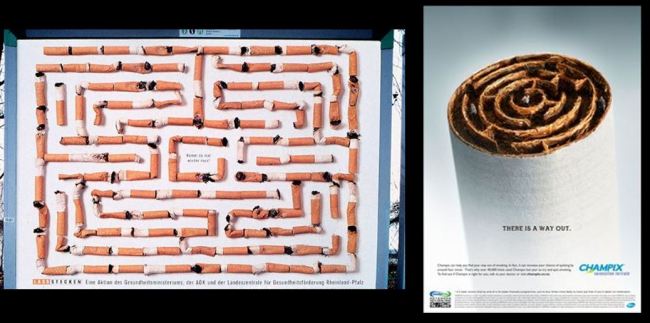

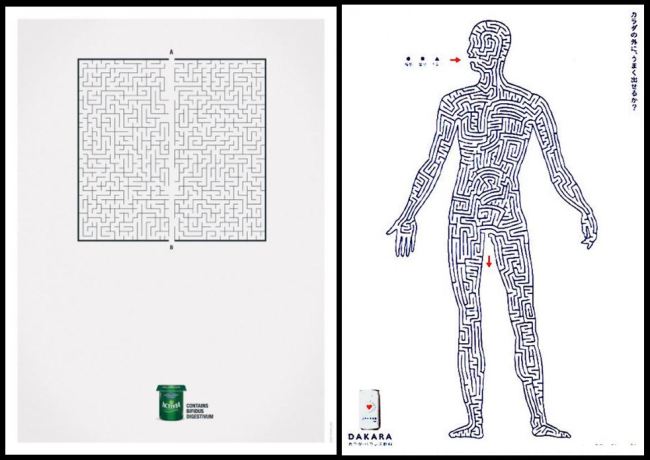

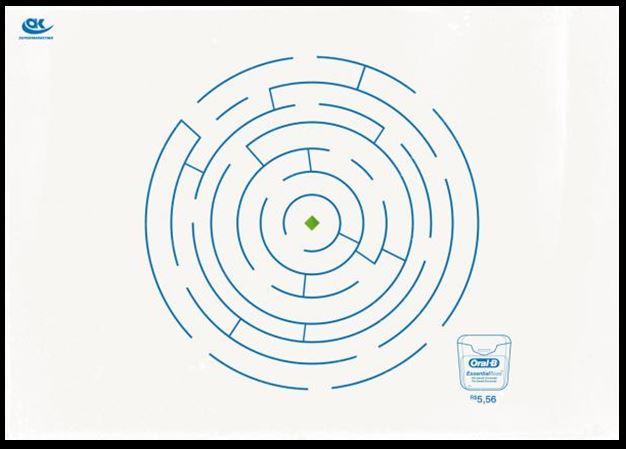

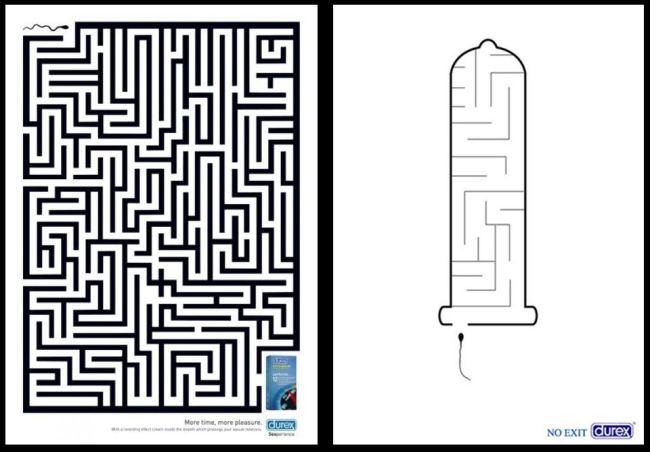

Labyrinths and Mazes in Print Advertising

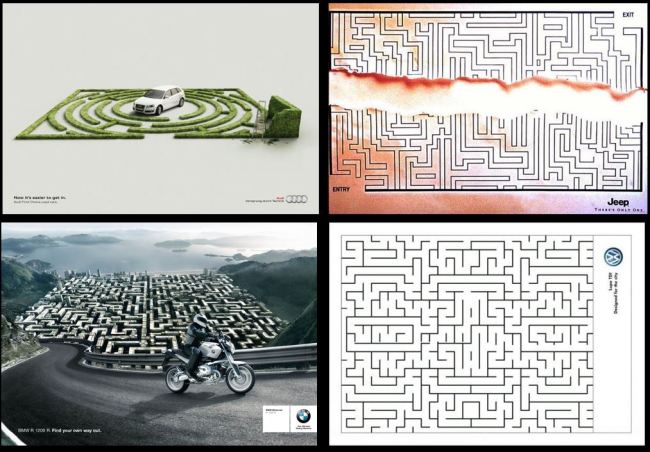

Print advertising is interesting because it has such a small amount of time to communicate its message. This means it has to leverage existing understandings, rather than trying to create complicated new ones. The result of this is that semiotically we can perceive many shared-understandings of the Labyrinth/Maze symbol.

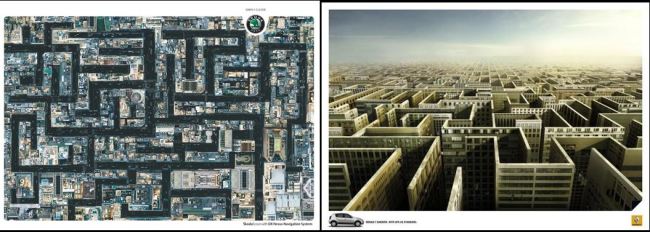

A dominant code is that the Maze is a barrier to mobility. Mobility is a central theme of modernity. Car brands speak of their vehicles as magical vehicles that render the maze passable.

Interestingly, these ads also frame modern living and urban cities as the labyrinth. Earlier, the symbolism of the underbelly of cities as a negative labyrinth was discussed. If we personify cities as people, they have a dark subconscious as well.

- Audi ‘Now it’s easier to get in’

- BMW ‘Find your own way out’

- VW ‘Designed for the City’

Skoda and Renault have both positioned their GPS systems as the ‘golden thread’ for navigating this urban maze

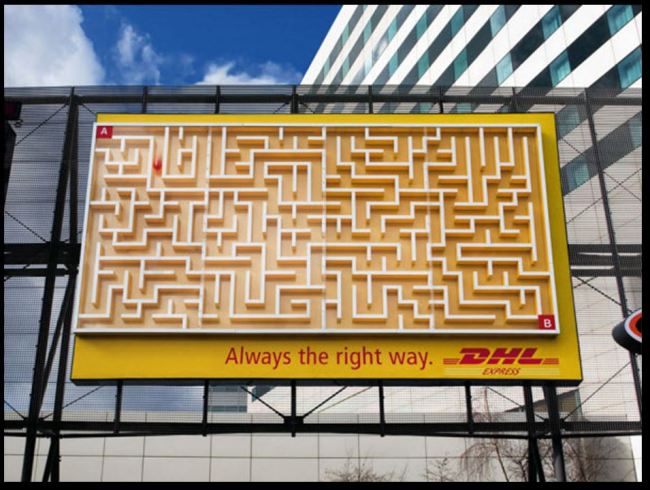

Related to this, DHL knows navigation and time-efficient delivery

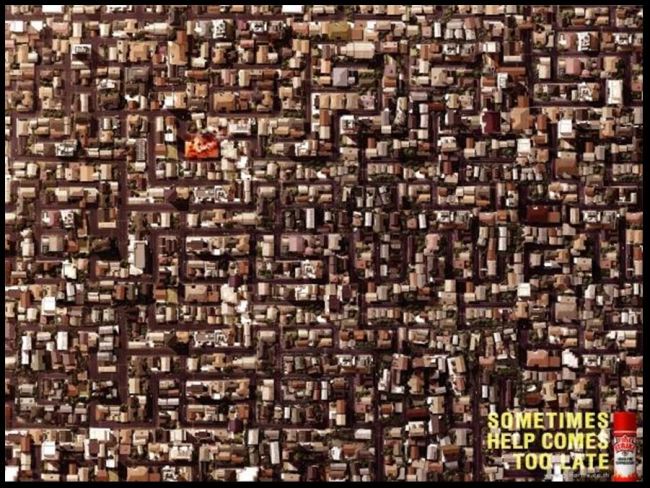

For a fire-retardant brand, they suggest the opposite; the realities of time and navigating are the proposition to stock their product for the protection in your house

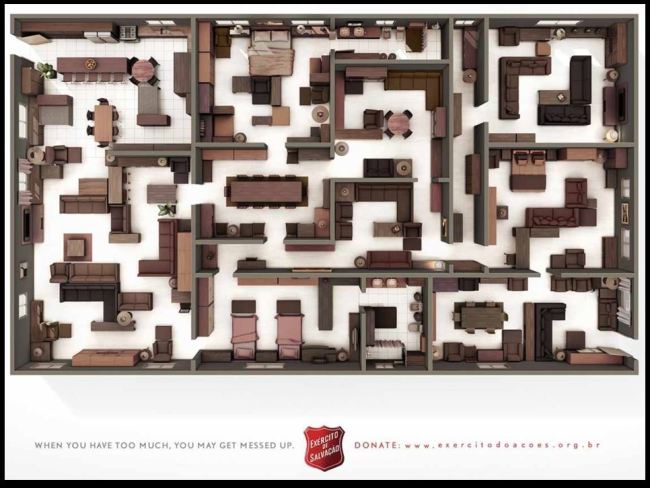

This metaphor that urban living is a maze has been spoken through different ways. The Salvation Army has suggested that we are making this complexity for ourselves.

City Harvest juxtaposes want with elite food addressing hunger

The maze is again used by anti-smoking campaigns to speak to challenges of breaking free

If some brands are speaking to barriers, the health industry uses the maze as a frequent visual metaphor for easy alimentary journeys.

Oral-B used a classical labyrinth to illustrate that, like the Golden thread, it could help you get to the right spot.

The reverse of this is also true in healthcare, where the labyrinth is used as a metaphor of containment

Durex has used different executions of the Maze to suggest containment. Although, the visual message of the first ad seems to be at odds with what they are selling. Yes it takes longer, but the sperm still gets through?

At the end of the path

When we consider the use of the labyrinth in movies, many appears to reflect many of the dystopian themes that I have discussed in early posts. Where we see the negative use of labyrinths, they are not being used has their historical symbols of spiritual renewal or rebirth but as metaphors of a complicated modern life to survive. There are a couple of themes here. Firstly, walls are perceived as barriers – this evokes our lives of challenges. Secondly, we live busy lives with broad expectations ‘instant gratification’ and anything that expects us to slow down and think are ‘irritations’. Movies reflect back the myths that we want to resolve, so while this might appear negative, the labyrinth is a powerful psychological symbol to make us think about how we overcome these challenges in life.

In advertising it is difficult to see the labyrinth; it is mostly the maze that is used. Many ads in this space appear to suggest that we perceive our urban lives as complicated, confusing, constraining and needing a lot of attention. They don’t reflect back the labyrinth’s journey to the centre; they suggest more a desire to get out of the maze or find a way to bypass it.

It’s clear that the different meanings labyrinth and maze are still experiencing some confusion today. The start of this discussion was the global trend in labyrinths that we can physically immerse ourselves in an experience. Interestingly, this is closer to the primordial purpose of the symbol. Our needs in a fast moving, more abstract and fragmented world to experience something where we are both challenged but lead to a sense of getting to the deeper part of an experience, rather than just have our frustration reflected in a maze. Perhaps in the continuing postmodern project, we are all looking for a golden thread to follow.

It’s probably why a printed circuit board looks to artistic and fascinating to us – appeals to human imprinted mental development. If you go to Mykonos on the Greek Islands the streets are narrow and like a ‘labyrinth’. The villagers know the layout but the complexity confused any invaders giving both an escape and easier defence as the enemy hoard was narrowed to a single file. This can’t have been the only community to see this as a defence – even Cornwall villages have narrow streets hardly wide enough for a donkey. Moroccan souks are also a maze that only locals can navigate, maybe that had an advantage not currently needed.

That city structures that had a ‘maze’ like design might have been a military adaptation is an interesting observation. There were definitely ‘kill boxes’ built into some city designs. The home-court advantage would certainly go to the local populations.

I didn’t really touch on architecture, due to the growing size of this post. But there is a tradition of architecture being based on labyrinths, Antonio Averlino’s Design (Filarete) for the castle of Sforzinda, which he describes in the Codice Magliabechiano, is a well known architectural labyrinth from 1460 AD. Even Paris is organised around a spiral that radiates out from the centre of the city.

In Umberto Eco’s “the Name of the Rose” part of the Monastery is shaped like a maze in order to hide particular literary works. So, mazes can work to obscure and confuse those that don’t belong.

These architecture features weren’t always ones that you moved around. The Dome by Francesco Borromini, view of the dome from inside, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome, 1638-1641 – shows a geometric labyrinth.

Pingback: Why are we no longer in love with our Cities? | :: Culture Decanted ::

Reblogged this on A blog and commented:

Mazes and labyrinths as archetypes of humanity

Reblogged this on LuciaLeão and commented:

imagens de labirintos na cultura.

Pingback: Westworld, Delos, Gnosticism, Alchemy and Jungian psychology (Did I leave anything out?) – 4 Ever Bored

Pingback: The Westworld Finale: A Reading List for Dolores : The Booklist Reader

Pingback: Mazes and labyrinths research continued – Vita's blog

Pingback: Find Your Center: The Twisting Tales of the Maze and Labyrinth

Pingback: Threading a Maze – Start-Up

Pingback: Puzzle Prompt Creative Challenge ~ April 2023 – The Black Collar Bugle

Many thanks. Marvelloius and inspiring what you put together here.

Many thanks