Tags

Vigilantism and Justice in modern society: a popular culture analysis

Vigilantism and Justice in modern society

The last few years haven’t been good for law-enforcement agencies in Western countries. There are many examples of both police and public failures of trust. While relationships are strained, in practice, the vast majority of law-enforcement are commendable civil servants; as are the majority of citizens who appear to respect the police and the service that they provide. However, increasingly, our law enforcers are not held in the same esteem that they once were. It is interesting to ask, why? What has changed these perceptions?

I started becoming interested in the influence of popular culture on our perceptions after a conversation with a friend where I was criticising the dilution of the law through many aspects of modern storytelling. For example, I stated that many TV shows have fallen into the habit of the coercing cooperation through unsanctioned threats of violence, rape and death that will happen in jail, rather than the existing legal penalties. It is easy to find examples of this from TV, on the long running Law & Order franchise, to films like the Siege. If the trump card in these stories is what criminals will do to each other, rather than what the system will do to them, in some ways this can be seen as passively endorsed criminal behavior.

What does this suggests to the audience? That law enforcer’s lack conviction of the legal system they are part of? Is there a need for more persuasive penalties than we currently offer? This is a curious discourse for many countries that have dropped the death penalty as part of the legal system, but in our stories we often read or see the combined threat of our legal system’s penalty plus the threat of unsanctioned violence or death. This could be another symptom of the postmodern condition; having de-fanged the threat of eternal punishment from religion, do we need a hyperbolic threat in the near future to motivate lawful behavior?

I know that some reading will point out that it is easy to separate entertainment and fiction from reality. Don’t we all agree to suspend disbelief about these approaches to law because it makes for some exciting storytelling? Rationally I agree, however, I suspect the cumulative and consistent framing of law enforcement is starting to shift perceptions in the western world.

This is the second part of some thinking about the law in popular culture that I have been writing about. While the previous post focused on the nature of Justice, this post is focused on those that enforce the laws. A hypothesis explored in the previous post, and expanded here, is that popular culture is framing the way that many in western cultures perceive the law, the legal profession and our law enforcers.

There are many crime story themes, structures and tropes from a semiotic perspective that frame the way that we think. The continued experimentation and development of these narrative elements is resulting in a continuing shift in public perceptions about law enforcers. The following presents an exploration of some of those that appear more influential in contemporary storytelling.

There are two parts to this discussion:

A: Justice and Vengeance – who wields the sword of Justice in popular culture?

B: Perceptions of Modern Law Enforcers in Popular Culture

Part A: Justice and Vengeance – who wields the sword of Justice in popular culture?

Good, Evil and the Law

Continuing a thought from the preceding post is that Justice is something that is not necessarily moralistic. However, we tend to perceive the perception of law in moralistic terms.

In very general terms, this positions most perceptions of law-enforcers around four quadrants of meaning:

- Good/Law: The guardians or keepers of the law – those that enforce the law.

- Evil/Law: We recognise that corruption is part of law-keeping – where individuals might partake in the abuse of their power for personal gain.

- Evil/Outlaw: Criminals act outside of law; they are not part of the civic body.

- Good/Outlaw: There is a grey area where people break the law for good reasons, e.g. being a whistle-blower.

It is in the enforcement of law that we see the ‘grey’ areas present in the Good/Outlaw quadrant that are most informative about society today. This is a contradiction that can be perceived in different ways. While the opposing quadrant of Evil/Law is more black and white, the Good/Outlaw quadrant is potentially good or evil depending on your starting perspective. The recent actions of wikileaks or Edward Snowden have been discussed from different sides of the media ring as being either criminal or heroic. The actions of vigilantes are likewise discussed as being those of a person delivering Justice or an individual taking law into their own hands.

Revenge is an act of passion; vengeance of justice. Injuries are revenged; crimes are avenged.

Samuel Johnson

A righteous murder?

There has been a consistent drive across cultures for extra-legal justice, driven by the relatable need of the victims of crime to want or seek their pound of flesh. In the Old Testament this comes from a law of ‘Lex Talionis’ or ‘an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth’ – justice that is balanced as by Justitia. Considering the drive to ‘take the law into your own hands’, there are many belief systems that have deities seeking to limit this drive directly. By making justice a divine responsibility, this defuses the need for continuing reciprocal feuds. So it is easy to find many cross cultural examples; in Egyptian mythology, Sekhmet is seen as the goddess of vengeance as ‘she who mauls’. In Greek mythology, Nemesis was the goddess of divine retribution and revenge; Adrestia was the goddess of revenge and retribution; and the Furies or Erinyes were deities of vengeance. In Judeo-Christian contexts, the right to balance the scales of justice for those that don’t appear to be punished enough, there is exclusively the province of God. In many cultures, belief systems provide a consistent restraint on this primordial impulse of humankind for revenge. In a modern and more secular world we don’t have this omnipresent constraint.

If we look at the way that Justice (as an outcome of Jurisprudence) vs Vengeance can be understood in contemporary stories, it can be mapped across the following meaning dimensions.

Here there are more personal vs societal implications of justice. Additionally, there are differences in the humanism involved in capital punishments and the arguments for both sides. This can be illustrated easily by looking at popular culture.

There are four themes for story telling around these dimensions:

- Punitive-Justice: “Judge, Jury and Executioner” – there are two prominent trans-Atlantic examples in Dirty Harry or Judge Dread of Megacity One in 2000AD comics. Both men unilaterally dispense of justice on the spot as they see it.

- Corrective-Justice: Heroes like Superman and Daredevil live by moral codes of non-lethal force. They apprehend criminals but are also known for dispensing looser-justice on occasion where there are grey areas.

- Corrective-Vengeance: A darker space; anti-heroes like Batman seek vengeance for their personal tragedies. With little restraint, just short of death, they apprehend criminals for incarceration. More recently, the horror series SAW explores a serial killer that illuminates through corrective vengeance that includes grisly murders.

- Punitive-Vengeance: The vigilantes that take the law into their own hands and operate outside of the law. Frank Castle in Marvel Comics, a devout catholic ex-military who turns homicidal crime fighter after his family is killed by drug dealers. In many ways, denouncing God to take vengeance into his own hands.

A vigilante is defined by the OED as:

A member of a self-appointed group of citizens who undertake law enforcement in their community without legal authority, typically because the legal agencies are thought to be inadequate.

Vigilantism appears to rise when there is a perception that the system is no longer functioning. When NYC was struggling with high crime rates, Berhhard Goetz, in 1984 shot four men and was dubbed the ‘subway vigilante’. This is one of many examples that can be found globally. These accounts involve a citizen taking justice into their own hands.

In popular culture, most vigilante stories are influenced by the crimes that create, define and drive them. Many are variations on the influential Batman story, recognising that Batman was influenced by earlier vigilante stories such as Zorro, The Scarlet Pimpernel or Robin Hood. Batman was a definitively more urban, modern and darker psychological telling of this original story. A modern interpretation of the Batman story is serial killer, Dexter. It is easy to see the many similarities between these two characters:

Dexter is a modern version of Batman in a society that is looking for a different kind of hero to challenge the evil we perceive around us.

The vigilante remains a favoured theme by Hollywood and its audiences, there are many variations on this subject

Part B: Perceptions of Modern Law Enforcers in Popular Culture

No one likes to be told what to do

Law Enforcement gets a bad rap, after-all, who likes to be caught doing something they shouldn’t? They are the human face of often black-and-white rules that subjectively appear unfair, like parking tickets, etc. Additionally, being part of the establishment, police are often perceived as being the arm of the ruling classes. Often, when there is societal discord, this paints them as the agents of oppression, rather than the guardians of the law.

When annoyed by them, we tend to think of law enforcement in derogatory terms, such as ‘pigs’.

Although, the origin of the word was more positive when it was first introduced, it has overtime become more derogatory. The first English Constabulary were called ‘Bobbies’ or ‘Peelers’, after Sir Robert Peel that commissioned their service. The OED cites the use of the word in relation to a ‘Bow Street Runner’ in 1811 – the location of the first headquarters, these police where attached to the Bow Street Magistrates office. The continued association of police with ‘pigs’ have led to popular culture icons such as Chief Clarence “Clancy” Wiggum from the Simpsons, characterised by his piggish behaviour in being stupid, lazy and prone to gluttony. Al Jean, a creator, has admitted, the porcine nature of Wiggum is a ‘conscious pun’. The Simpsons did not create this stereotype but they have helped to reinforce it.

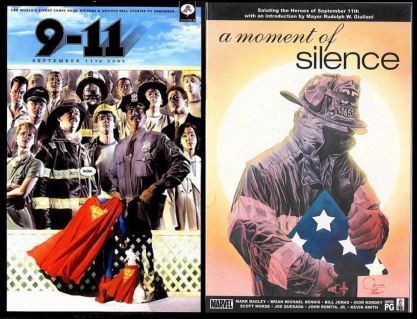

To be balanced, popular culture has also shown a great deal of respect and appreciation for the sacrifices made by law enforcers. A notable example was after the tragedy of 9/11

Is there an ability hierarchy in Modern Law-enforcement?

“Anxiety is the handmaiden of contemporary ambition.”

Alain de Botton, Status Anxiety

As social apes, we are wired to be personally and socially competitive. This introduces hierarchies into many facets of society and culture. As a result, we are wired to expect hierarchies in society and culture and draw conclusions from these associations. Stories introduce and frame our law enforcement agencies as hierarchical organisations. There is a consistent message of elitism, true or not, in the way that Hollywood tells its crimes stories. For example, we can look at the main branches of law-enforcement on two sides of the Atlantic.

An implication of this model suggests that the visible arm of law-enforcement are not the best and brightest, just the able and willing. While I don’t believe this distribution of talent is true, I do believe this is a frequent message from contemporary crime stories. Think of a TV show or film where the person went down this on this model, it isn’t framed as career diversification or development, it’s never a promotion. How many times do we see detectives demoted to being beat cops, e.g. in Lethal Weapon 3, Riggs and Murtaugh were put into beat cop uniforms as punishment, demoted from detective Gold to Silver badges. In simplistic terms, in Hollywood, not wearing a uniform is a promotion in law enforcement. Does this imply that the law enforcement officers we do see in uniform are not the best? There are increasingly less uniform cop shows on TV which would contribute to this impression.

It is possible the recent surprise by some American commentators at seeing a paramilitary response to several situations in 2014 is related to this model. This was not just a reaction to a more militarised America and a belief that domestic police were now over weaponised. Some commentators at the time were discussing these paramilitary cops as playing out some dream of being soldiers. Seeing people we don’t think of as being elite dressing up as elite soldiers can create some concerns.

From a different perspective, this can be seen in a review of the Video Game, BattleField Hardline, Chris Plante opines:

Battlefield Hardline moves the Battlefield series from international battlegrounds to a realistic domestic setting: As tricked out police, the player in Hardline uses heavy weaponry, armor and vehicles to kill criminals in Los Angeles. Despite the move, the series’ fetishization of military weaponry, gear and lethal combat remains.

Cops and soldiers are not the same thing. They serve different purposes. Soldiers often serve in war zones, in direct conflict with our nation’s enemies. The police serve in our cities, protecting and policing our nation’s civilians.

And so Hardline is an uncomfortable role play within a role play: the player pretending to be a cop pretending to be a soldier.

With over a decade of living through the ‘war on terror’, the traditional roles of policing are evolving to meet a different type of threat. As much as there has been a change in policing, there has also been increasing light shed on the less-visible parts of a countries law-enforcement.

Stupid is as Stupid Does

Another way to consider how popular culture shapes the way that we perceive law-enforcement is how these stories solve the need for narrative-tension. Without a tension, something to correct or resolve, stories are merely passages of words. Without tension they lack the emotional resonance that we identify and engage with.

Stories use different tensions to create different dimensions of tension and suspense. In crime stories, a frequent trope is that of the system getting in the way of the ‘good’ cop. This is done in many different ways. At a broad level, we are shown law-enforcement with different levels of intelligence on a regular basis depending on the protagonist. For example:

The police in Law & Order are all competent crime fighters but are frequently frustrated by the different layers of bureaucracy often holding our heroes back from making their case. In Bones, FBI Booth is paired with a forensic anthropologist in a classic IQ/EQ tango, where intellect-vs-insight misunderstandings often create the tensions.

However, in some stories the police are framed as ‘fools’. In Dexter, the police are framed as being unobservant, as we see their ignorance of the bleeding-obvious through the eyes of a serial killer. In movies like Beverly Hills Cop, the grounded Axel Foley shows the naïve soft cops of Beverly Hills everything from proper detection to how to insert a banana in your exhaust. The implication here is that we are shown that not all police are equal on a very regular basis.

Writers often use the different branches of the law to create a tension due to who caught a case and whose jurisdiction the case falls to. In American series, a very frequent tension here is between normal police and the FBI.

In the film franchise Die Hard, feet-on-the-ground, yippie ki yay, recalcitrant NYC cop John McClane, is contrasted with the arrogant, sunglasses-at-night, FBI agents. You’re left in no doubt which branches of law-enforcements are fools; actually, the criminals in the film factor the rigid thinking of the FBI into their plans. In contrast to this, the long running serial, Criminal Minds, often hits tensions with local police enforcement who resent their taking over of the crime scene.

The net effect is that we are asked by different crime stories to believe that both the FBI and normal police are ‘fools’ and ‘smart’. Watching any show, we look for insight in the expectation of this dichotomy. With films like the Blues Brothers 2000, amongst many others, depicting them as unthinking lemmings, is it any surprise that we might question police actions?

[embedded video]

Mythic Considerations of Crime Fighting

‘There have been times when a danger upon the world…required the services of singular individuals’.

A further consideration is that some stories introduce crime fighters that operate outside of the normal legal system. A convention in some crime stories is that the system is not capable of dealing with all threats. This is the space where we see vigilantes or self-appointed heroes arise.

It is a rich theme of mythology that heroes arise when societies need them. The mythical heroes of the current age of storytelling are the ascendant comic heroes, who are now dominating the big screen. Marvel is believed to be releasing 3-4 superhero movies a year, planned up to 2028; not to mention the small screen series that are emerging like Game of Thrones, Flash, Gotham or Arrow. Historically, heroes take many forms from Hercules, Sampson and Sinbad through to Captain America and beyond.

Why do we need mythic heroes? We can look deeper at the role of myths in storytelling, Claude Levi Strauss view was that

‘…myths help people overcome a contradiction they seen in the world by providing another contradiction, one that is soluble, into which the first can be absorbed’.

The idea that our police force is either corrupt or incapable of dealing with all of societies needs are contradictions that are being thought through in our contemporary stories.

Types of Heroes in stories

“For where might and justice are yoke-fellows – what pair is stronger than this?”

Heroes, come in two main types: Brawn and Brain. Following the conventions that have been discussed above, many of these stories are about heroes that operate within the establishment or on the fringe.

- Physical / Establishment – These shows celebrate the alpha male taking down the criminal through a hunting metaphor. The rebooted Hawaii Five-O is a show that savours its criminal flight and takedowns. The show celebrates the fitness of its key actors taking down criminals through every imaginable square foot of Hawaii scenery. A couple of decades earlier shows like TJ Hooker were similar hunting and catching shows.

- Physical / Non-establishment – These are shows where they are physical but are outside of the usual police establishment. The film SWAT shows the development of an elite paramilitary unit, compromising of misfits who come good. Although, aspects of shows such as Nikita (any of the three main versions) fit into this quadrant.

- Mental/Non-establishment – The many Sherlock inspired shows fit into this quadrant. Intellectual assistance by a preternaturally gifted individual in deduction: Sherlock, Elementary, Mentalist, etc.

- Mental / Establishment – Rise of the nerds. The true hero of science has its many faces in shows such as CSI, NCIS. The supporting characters are brought to the front assisted by ever-receptive detectives that wait for their instructions.

These basic meaning quadrants of Brain/Brawn or Establishment/Non-establishment can be found in many different forms. They can also be found working within the one narrative. For example, the movie, The Untouchables

Here the story was structured around these four narrative quadrants (historically there were ten men in the team that Ness led). In the real world, Elliot Ness was a fan of Sherlock Holmes and there are indications he tried to imitate his methods, which is why he is in the mental quadrant, even though he is educated to the physical by Malone across the movie. In the film version, the team were successful because they operated outside of the legal system in many ways; they were a force that society needed from the outside – a mythical hero. Hence, George Stone was a rookie and Malone a cop, being punished for not fitting in was walking the beat to retirement. These are both officers that are not part of the corrupt police force of the time. Ness and Wallace were agents who operated outside of the system being FBI agents.

The pen is mightier than the sword if the sword is very short, and the pen is very sharp.

Terry Pratchett

An analysis like this cannot attempt to cover all story permutations, so I am deliberately leaving aside comedy. From a thinking perspective, if we take Sherlock Holmes, it’s easy to find the more humorous examples of this in Peter Seller’s ‘Inspector Clouseau’. One of the most parodied crime fighters is James Bond 007, by characters such as Get Smart or Austin Powers; the IMDB lists 241 ‘spoofs’

Closing Comments

It is a convention that the sword of justice is wielded by the government of the day. In earlier times, the restraint on those looking for vengeance was tempered by the fear of divine retribution. In increasingly secular times where legal systems appear, at times to be blind to public opinion, popular culture has been a voice for this dissonance. Occasionally vigilantes have taken the law into their own hands.

A consideration here is that the continuing evolution of our crime stories frame law-enforcement and justice itself as sometimes ineffectual, leaving criminals less intimidated and good citizens in doubt that they will get the Justice they desire.

The way that we tell stories about our law-enforcement officers does appear to frame them in several less-than-positive ways. In summary, some of the main ways are:

1. Within popular culture, law enforcement is generally shown through relatively negative frames of thought.

2. With recent history showing that law enforcement practices of western democracies are not infallible. In some cases, there appears to have been the conscious bending of laws in the pursuit of vengeance over justice.

3. They raise questions over the quality and capabilities of all branches of our legal system.

As a result, if the earlier vigilantes were acting on the more physical sphere of taking justice into their own hands, there appears to be the emergence of a new class of modern intellectual-vigilantes. Wikileaks, Richard Snowden and even the Anonymous Hacking group are all prominent examples of this.

The emergence of such extra-legal forces suggests that the current legal system is struggling to deal with all of the changes of the modern world. Individuals are taking their concepts of justice and applying it outside of law that are representative of the broader community consensus.

A question to consider is whether popular culture is merely a reflection of this reality, a harmless imaginative exercise that has no real influence; or an evolving anthology of stories whose meaning and structures are slowly eroding confidence in the legal system. We’re a long way from the days that Police arrested criminals by telling them to “stop”. If our elite law-enforcement doesn’t wear uniforms, their unsanctioned counterparts in justice don’t either.

Pingback: “Fortunately, I am mighty”: How the Avengers Demolish All Motives and Consequences – Electric Didact

Pingback: Our Vigilante Society: Stating Your Opinion Is One Thing, but You’re Not Always Right (Part 2 of previous blog) | Bonnie McCune, author

On “Hawaii Five-O” the task force came

into being because of the corrupt governor of the aloha state, a woman

who was in cahoots with the main villain Wo Fat, but got her comeuppance, which McGarrett was framed for and jailed. I wish the writers had dug deeper by giving Pat Jameson a back story. Why was she supporting Wo Fat? Was he blackmailing

her? Was she hiding a past secret (i.e. teenage pregnancy) that would cause a scandal for her political career,and Wo Fat was holding it over her head? After all, corruption begins at the top. Governor Jameson did not

do the right thing. She failed the state of Hawaii. And her wrongs were never made right.

Pingback: Ms WALLIS » Blog Archive » UNIT 3: An Eye for an Eye