December

13

December

13

Tags

Is Popular Culture influencing our perception of Justice?

Why write about Justice?

Looking back, Justice and Injustice have made frequent headlines over 2014, in fact for most of the last decade. Whilst I’m not in the legal profession, I feel qualified to have an opinion, as I’ve being lawful across the span of my life (maybe Gladwell is right and having been lawful for at least 10,000 hours we are all more than laymen here). Like most people, I live by laws that I’ve never directly had a hand in writing. Perhaps this might identify me as a dutiful civic sheep, compared to the shepherd, sheepdog… or a wolf. Though ultimately, living in a democracy, we have the choice to vote in lawmakers that can change laws, to reflect how we think society should be organised. I don’t believe you have to be an in-law in order to have an opinion, if you’ll excuse the pun.

Upon reflection, I’ve travelled the world and seen different versions of ‘justice’ and ‘law’; I’ve lived in relaxed countries and more authoritarian ones. I’ve experienced cultures that challenge some of my foundational thinking about what human rights and Justice are; and been flummoxed at societies that appear erroneously litigious, e.g. urinating standing up is illegal after 10pm.

The first requisite of civilization is that of justice.

Sigmund Freud

A hypothesis is that over the last decade there has been significant erosion as to what justice means. There have been seismic shifts in the cultural and social fabric of the western world. Within the postmodern swirl of activity and change, it is the norm to challenge the establishment, the old dogma and the ‘grand narratives’. Enthused and enabled by social and technological changes, modern society continues to push and challenge many boundaries, with positive and sometimes questionable effects. These have been across nearly all spheres of modern life: religious, social, racial, cultural and political dimensions.

Within the very broad subject of Justice, I’m interested in the changing stories about justice that are told in popular culture. Historically, Justice was seen as being black or white, good or evil; there are now shades of justice and morality that dominate the ever-popular genre of law and crime. From a semiotic sense, what are the underlying structures behind many of these legal stories we tell? How are these changing in relation to an audience that is living in a rapidly changing world? (How) Is this changing our perceptions of justice in a modern world?

This is a big topic, so I’m going to break it into two posts:

- This part will focus on the symbolism of Justice and the structural aspects of Justice stories in popular culture.

- Will look at how perceptions of law enforcers are changing with popular culture as a result.

What is the symbolism of Justice?

The more laws, the less justice.

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Where do we get our symbolism of Justice from? What Justice is, has been a consistent topic of discussion from the earliest times. Is Justice is part of law or a moral judgment about the practice of law? How we talk about Justice and injustice can shed some light on contemporary perceptions.

The symbolism of law, like many western institutions is influenced by my different cultural and religious sources. We can look first at our common laws. If we reflect, many modern democracies share the same philosophical foundations of jurisprudence from the Judeo-Christian Ten Commandments. Even if you don’t believe in ‘God’, most modern western countries are living in a society based on beliefs descending from these ancient religious laws.

In a more secularised society, many have commented that the Decalogue has become less relevant and harder to interpret within modern times. Consider this; does the following description remind you of anyone? That you swear occasionally; don’t consider yourself religious; work hard, often over weekends; love your sport; struggle to see your parents as much as they would like; have wondered too-hard-and-often why people find the Kardashians or George Clooney attractive; believe you pay too much tax; and wonder why your neighbour has a better house than you, considering they are really rather ordinary? Allowing for a little bit of poetic license, loosely, you might have broken 9 of the 10 commandments. Murder is the only religious and social taboo that we won’t cross (well depending on your perspective on the death penalty, maybe some do).

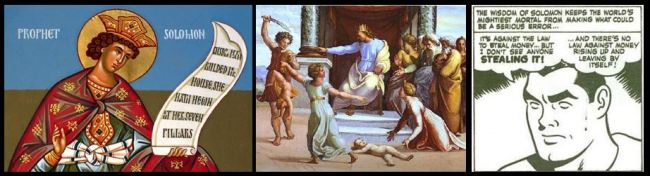

The penetration of the Decalogue for much of the west comes from its central role in the early Roman Empire and the codification of laws by the Emperor Justinian and following legal normalisation that followed. The Corpus Juris Civilis or Codex Justinianus was issued between 529 to 534 AD. These efforts of a common code of law created a more stable and sole source of law across the effort: introducing the significant innovation of culturally transferable jurisprudence. If this was the historical reality, the image of the wise judge and the role of the interpretation of law come from the bible in the image of the wise King Solomon.

It’s worth noting that, Solomon’s famous legal ruling to cut the child in half is a clever evocation of the Justice with its sword and scales (discussed more below). His ruling instructs that law must be mediated by wisdom and the understanding of human nature.

Justice and injustice over the last decade

Since my starting hypothesis is that perceptions of Justice are changing, it’s important to look at western-democracies and the prominent news stories over the last decade. What we see is the increasing erosion in the absolutism of law. I’ll only list a few examples here, there are many more (depending on your political leanings some of these might be over-or-under stated as examples of justice or injustice)

On both sides of the Atlantic, lawmakers have been shown to be breaking and stretching the law. Bill Clinton managed to mangle the very definition of what a legal lie is. The Gulf War raised many challenges to concepts of international justice, e.g. the American Government claimed that lacunae or gaps-in-law amount to the non-prohibition of an action, therefore not making certain behaviour illegal. English MP’s and law lords were shown to be stealing from the public purse through their expensive claims. There is the lasting public perception of the increased tensions between the 1% and the rest of us, exasperated by the lack of criminal charges against individuals for the GFC. In the religious domain, the Catholic Church has been criticised for its criminal handling of child abuse by ‘one in 50’ of its priests. More recently, maybe not that surprising to the citizens of many nations, shadowy government departments have been illegally surveilling each other and their own citizens. In fact, it’s almost too easy to find examples where the law has been ‘broken’ though exigent circumstances or fuzzy loop holes. It’s almost expected that some new political neologism will obfuscate behaviour that previously would have been unsanctioned. All of this is cumulatively creating an impression that injustice balances out justice; where Justice should balance out the law and criminality.

What are the mythical origins of our conception of Justice that influences its use in popular culture?

To understand Justice in popular culture as something separate from law, it’s important to realise that we humanise and identify with the concept of justice intuitively. We seem to have an innate sense of what we consider fair, just and right (although this varies by culture and over time). While law is discussed in the abstract, it is perceived as being something that is written down. Justice is personified – we give Justice a human face to match our own.

In order to understand our perceptions of Justice, it is worth looking at some of the ways it has been conceptualised and symbolised. Please excuse the brevity here – I’m going to focus on prominent themes; it would be very easy to go into a deeper discussion.

Greek and Roman mythology is as influential as the Bible in our understanding of law and justice. Moreover, many of this early Greco-Roman mythography remains relevant and influential in how we understand many concepts of law within society and culture today.

Justice is sweet and musical; but injustice is harsh and discordant.

Henry David Thoreau

Since primordial times, humankind has linked the enforcement of laws and Justice with the cosmos. This is the cosmological opposition of order to chaos, which is at the heart of many belief systems; order, chaos; dark, light; good, evil; etc. is the macrocosm to our own legal needs. This can be illustrated in early Egyptian beliefs. Ma’at was both goddess of balance, order, law and justice but also responsible for the order of the stars and the seasons. Ma’at and her brother Thoth (also responsible for science, magic, writing and judgement) were jointly responsible for balancing Ra’s boat in the universe; they were also jointly responsible for the judgement of the dead. How we live our lives as mortal beings were contextualised with the universe being in balance. Justice that is sanctioned and endorsed by religion has the aspect of everlasting judgement and importance; every action we make has eternal implications.

Later, the Greco-Roman traditions were more complex in highlighting different aspects of law and Justice (showing am influence of the older Egyptian belief systems). The Greek meta-conception of Justice was divine so we find other deities having roles here. Astraea, in Greek myth, was the Greek Goddess of Justice, who fleeing humanities dark side, ascended to the heavens to become the constellation Virgo (noting that Ma’at was a stellar goddess as well). Another leading related deity here was Themis, a Greek titan who represented ‘divine’ or ‘natural’ law. Her daughter with Zeus was Dike, who represented custom or law, judgement and conventional laws. Her symbols are the scales and are associated with the constellation Libra. Dike’s Roman counterpart was Justitia who was similar, but more typically wore a blindfold. In discussing these myths, depending on the time, there are many inter-related stories and properties. There are many other legal demigods and spirits that performed legal role, such as the Furies. However, the focus here is on the personification of Lady Justice as the figure used most commonly today.

Modern Traditions of this Symbolism

Many remark justice is blind; pity those in her sway, shocked to discover she is also deaf.

David Mamet, Faustus

In a symbolic form, Lady Justice appears in modernity in varying forms of the same theme. Justice is female; holding the scales of justice in clothing that evokes the Roman era, holding a sword of her power. She can be shown as being more or less maiden-like depending on the influence from either Astraea or the more mature, Themis. The main contemporary difference is whether she is shown blindfolded (connoting impartiality) or not.

This ‘blindness’ has been a theme through popular-culture. There have been various different permutations of this theme. Back in the 90’s, there was the short-lived TV series ‘Dark Justice’ with its signature call-to-action ‘Justice might be blind but can be seen in the dark’. In this story, the Judge is also a rebellious vigilante by night. Dispensing justice of a night, for criminals that aren’t found guilty by jurisprudence in his court room.

[embedded video]

There were other series such as: Blind Justice where ‘NYPD Detective Jim Dunbar returns to work after being blinded in the line of duty’.

These shows were heavily influenced by the Marvel character ‘Dare Devil’ also known by his alter ego, Matt Murdock

Created by Stan Lee and artists Bill Everett and Jack Kirby in 1964, Matt Murdock wears a ‘Dare Devil’ costume to patrol the ‘evil’ that is present in ‘Hell’s Kitchen’ New York. As Matt Murdock, he lost his sight in an accident as a child that gave him ESP ‘sonar’ powers. Seeking to avenge his father’s murder by criminals, during the day he fights as a blind lawyer for justice as a defense lawyer, and at night he is a vigilante that fights evil more directly. This plays on this tension of Lady Justice being blind, innocent, but also holding the sword of action. Many of the Dare Devil story lines revolve around moral dilemmas, situations where an individual’s interpretation of law is stretched and challenged.

Are Justice and Law mutually exclusive?

At his best, man is the noblest of all animals; separated from law and justice he is the worst.

Aristotle

When we look at the use of the structural meaning-axes of ‘Justice’ we can see there are consistent uses of meaning. There are degrees to which we behave within the law (or outside of it), that structure many stories that are centred on the law.

Much of modern depiction of Justice in popular culture appears to revolve around the tension of Justice and Jurisprudence. Often questioning the ‘letter of the law’ as something very different from the ‘spirit of the law’. Justice has a qualitative dimension that functions beyond the written law; as the practice of law has been defined as an interpretative practice. From a moral perspective, Justice can be defined as operating without a written law.

Justice, n.

- Administration of law or equity.

- Maintenance of what is just or right by the exercise of authority or power; assignment of deserved reward or punishment; giving of due deserts.

From a legal perspective, Justice and law appear closely related. However, in more lay terms, there is a perception that laws are inflexible whereas Justice is meant to be about what is right or wrong. This sets up a tension ‘Emotion is unalterably opposed to reason and thus to Justice itself’ (Pillsbury). Perhaps in frustration with a legal system that has too many perceived bias, unfairness and inconsistencies, many rally behind the Old Testament sentiments of ‘lex talionis’:

‘But if there is serious injury, you are to take life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise.’ Exodus 21-24

In modern narratives, the rational application of Justice is often juxtaposed to the emotional demand for exacting justice that verges on revenge. It is this tension that is a core component of many modern crime stories that I shall explore more in the following post.

A Semiotic Structural Model of how we use Justice in Narratives

At a structural level, there are two axes of meaning when it comes to Justice Stories:

- Those that follow the law and those that are criminals

- Those that are within the system and those on the outside

Within this model of justice we can identify four quadrants of meaning:

- Lawful: Those that enforce the law and justice of the majority (or governing elite)

- Rebel: Those that resist the law or the rulers; defined as criminal behaviour they still are beholden to laws they recognise in who they rebel for (this is a social dimension).

- Anarchist: Those that refuse to accept any perception of laws; they act outside of legal systems and conventional morality.

- Corrupt: Those that are unlawful; they are usually within the enforcement of laws but are acting for personal gain.

If we look at the history of the crime genre, the first two examples are established icons of storytelling. The final two are relative newbies to popular culture.

What we see are two phases of storytelling across this matrix in modern narratives:

The first Phase focused on the direct binary-opposition of Good with Evil: Lawful with Criminal. There are a range of TV series that balance out the forces of Law and Order or CSI (hyphenate a city here), that present stories about the balance of the battle of good and evil. I’ll discuss these series in more detail in the second part of this topic in a separate post.

What we are seeing is that the second phase is becoming the more frequent way to tell crime stories. While not totally replacing traditional stories of an almost Manichean perspective on the battle of law vs crime, these stories are changing our perceptions of the protagonists and antogonists.

The second Phase has two story arcs.

- Corruption Stories: There have been a series of corruption storylines such as Black Rain , The Shield or Shawshank Redemption that have focused on the tension between Corrupt Law officials and the Lawful.

- Legal Rebel Stories: More recently, as we the audience have descended into a modernity-malaise where the system is broken, we have seen stories focusing on ‘rebel with a cause’ narratives. The battle is by the morally correct individual that is framed as fighting against the inertia of an almost totally corrupt system. A system that appears incapable of curing itself.

We can explore this through a wide range of examples of stories that invoke a sense of Justice and Law.

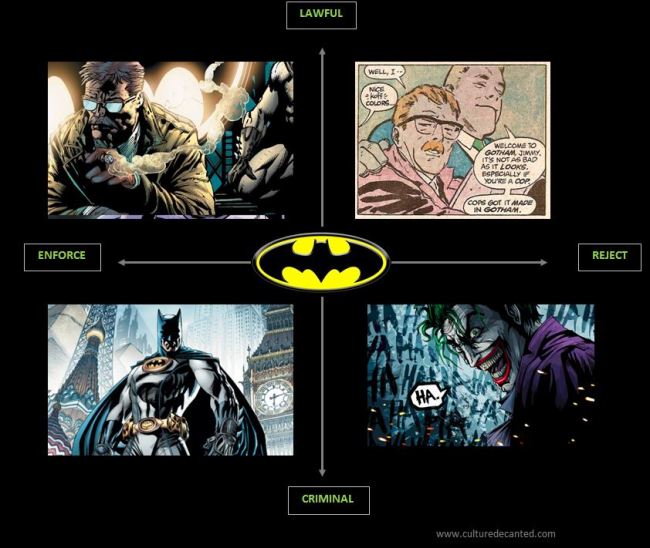

Batman: Story Structure

One of the giants and originators of this story arc, is the ‘Batman’ mythos by Bob Kane

Here we can see the role of the ‘Dark Knight’ representing the meaning-quadrant of ‘enforce law/criminal’ which is the opposition to a corrupt cop. Likewise the law/enforcer, in Police Commissioner Gordon, is opposed by the anarchist criminality of the Joker. When writer’s talk of Batman and the Joker being different sides of the same coin, that coin is in how they relate to law as both being not-legal. Batman fights to protect the innocents from an impotent system; whilst the Joker is almost post-moral thought the intensity of his insanity. Together, Batman and Gordon are a different reflection on being a ‘detective’ for good from within and outside of the system.

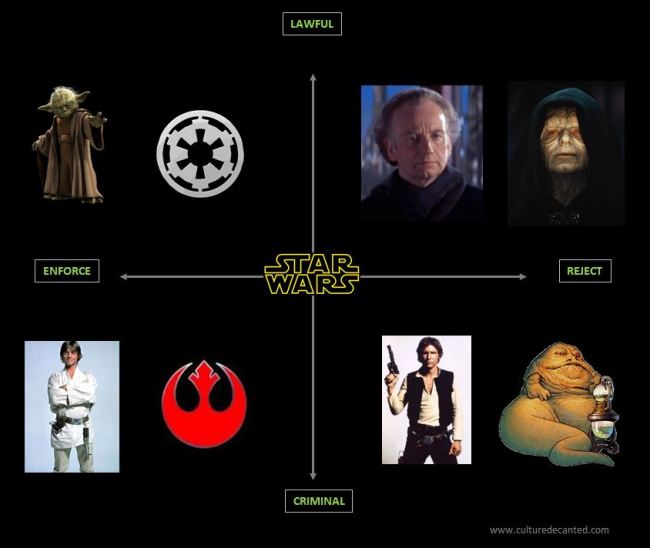

Star Wars: Story Structure

This structure of Justice can be applied to more multi-generational telling of stories, such as George Lucas’s Star Wars triple-trilogy.

The models above shows how different generations of the same story are represented through individual and collective protagonists across these dimensions. In the first trilogy, the focus is on Luke, Yoda, the Emperor and Han Solo. In the Second trilogy, the collectives are the focus: the Empire, the nascent Rebellion, the Senate and leadership of Senator Palpatine, the collective corruption figure headed by the Hutt (Jabba Desilijic Tiure).

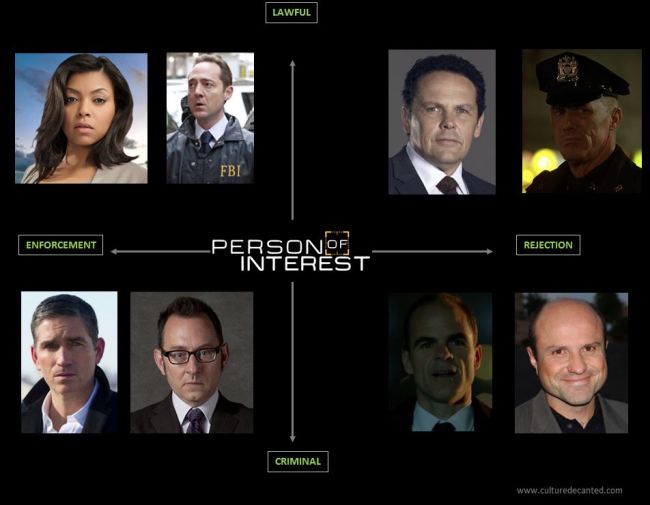

Person of Interest: Story Structure

A more modern telling of this story can be seen in ‘Person of Interest’. Here the mythical spirit of ‘Justice’ is replaced by an artificial intelligence. This omniscient computer system can predict crime by observing everything we do. Built to recognised threats to a post 9/11 world, the computer remains motivated to communicate all crimes to one of its creators, perhaps suggesting digital morality. Interestingly, it identifies potential victims blindly by numbers (evoking Lady Justice).

Here we see all four articulations of Justice expressed through this meaning matrix. The good cops opposed to the corrupt police, collectively known as HR. The former lawful protagonists of the story are ex-CIA and fight against the corruption in the CIA and criminal world.

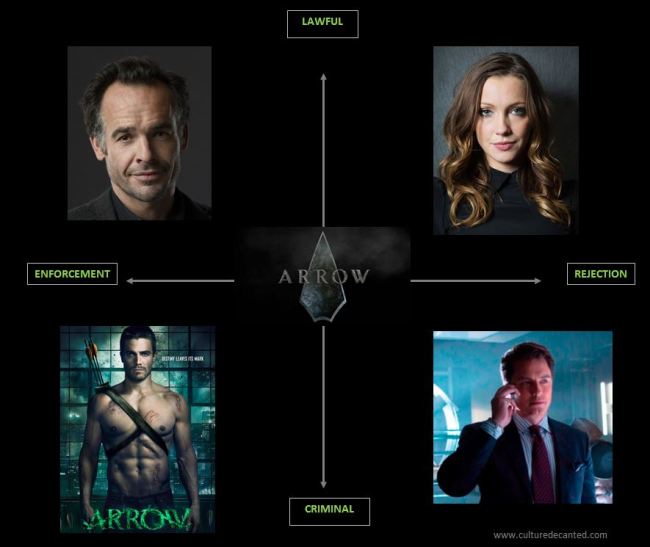

Arrow: Story Structure

If we think through the perspective of the righteous vigilantes of the Batman mythos, new series like Arrow (Green Arrow) still evoke similar dimensions of meaning around Justice. This is an interesting version because Green Arrow’s origins are a very obvious modern telling of the Robin Hood story. In many ways, Oliver Queens’ genesis was a more fun reflection of the Bruce Wayne and Batman storyline. Both are Billionaires, both have sidekicks, etc. However, the current TV series is as dark as the Batman storylines.

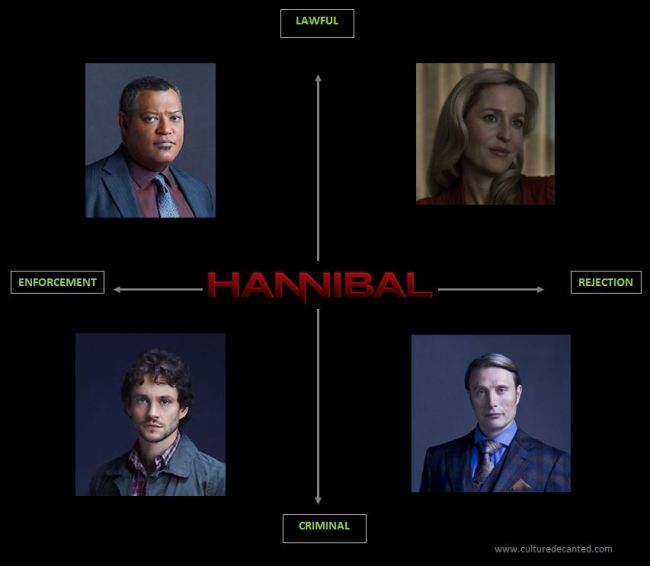

Hannibal: Story Structure

Over the last decade, there has also been the emergence of the serial-killer genre where these anti-heroes, as protagonists, mix-and-blur what the ‘antagonist’ really means within these narratives. I’ve used Hannibal here, but Dexter follows almost the same structure.

Some Judgements

Is it just a reflection of the post-modern mood that we don’t trust the establishment? Or, is the story telling we are seeing influencing our growing mistrust of the law and their ability to deliver Justice?

If we look at the current storylines, we see that there is a tendency for the starting point to be the assumption that the entire system of Justice is so broken that only a morally-minded individual can attempt to cure the corruption from the outside, rather than from within. Good cops are rare, isolated and ineffectual in a world of corruption or ineptitude.

What we see is that there is a call-to-action within these stories for all of us to act as individuals to make a change; that one person can still effect change. They evoke the much quoted thought

The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.

This type of message resonates on a more mythical level. Bob Cane was influenced by Zorro to write Batman, and Green Arrow in Robin Hood are revolutionary figures. These types of literary archetypes speak to a deeper mythological role of seasonal change. In seasonal springs, this is the triumph of spring over the entrenched winter; the spring prince challenging the winter king. This is Robin Hood challenging Guy of Gisborne, representing the old and stagnant order, being replaced by the new order. All of the modern crime stories evoke the need for revolution.

This raises two questions – if popular culture is a reflection of realpolitik

- Is it just fiction or do we believe that the lawful side of society is contaminated by the ‘corrupt’?

- Do we think only the rule-breakers or system-challengers are those that can fight for the laws and justice of the majority?

In a post-Snowden and Assange world this raises some interesting questions about how change will happen in an increasingly ‘by-default’ authoritarian world as technology seamlessly enters every part of our lives. If increasingly, our stories have are shifting to themes that the system must be fixed from the outside, what does this say about the coherence of society? Does explain the rise of new political parties, defining themselves as not being part of the establishment? Perhaps the question is not how long will Lady Justice be blind, but how long we are willing to keep the blinkers on for?

In reading this my mind quickly went to the very early age that justice and injustice is felt by children. With no formal education pre-schoolers feel the need for justice – another child stealing a toy, an unfair distribution of food or treat, a parental promise broken ‘but you said…’ rings in every parent’s ear. However, the modern world strives to be just. The more civilised a nation is the more complex is the law and the legal system. Judgements, appeals and high courts seek to establish the truth of justice through a chain of progression reflecting mature and educated lawyers. In Europe a nation’s legal minds and appeal systems are defeated by appeals to the EU court in a never ending test of justice. At least we have in modern times a system devoid of religion’s dogma with twisted interpretations of ‘old religion’s’ rules.

Marvel comic characters dispensing instant justice perhaps reflects the frustration of conventional, slow and policy driven law enforcement and the insecurity of the legal system who’s judgements do not always reflect community expectations of justice in a weak sentence (Pistorius?) If I were a superhero I would do wonders with my perfect dispensing of justice!!

To your earlier points, as I quoted Cicero ‘The more laws, the less justice.’ I’m not sure a profession that was traditionally paid by the ‘word’, hence incentivised to be more arcane in its language, is proof of a society striving to be just. I think we are born, as Haidt suggests seeking some innaate psychological balance of just with unjust.

I’m going to talk more to the forms of Justice and its enforcers in the next post. If this post was an exploration of the deeper narrative structures,it’s also clear that the law-keepers are as influenced by modernity as our perceptions of justice.

Pingback: Vigilantism and Justice in modern society: a popular culture analysis | :: Culture Decanted ::