September

21

September

21

Tags

Why are we taking the super out of the supernatural stories: another postmodern symptom?

Why are we taking the super out of the supernatural stories: is this just another postmodern symptom?

There has long been a casus belli of modernism and postmodernism to try to explain the religious, spiritual and supernatural, to find the rational explanation for events. While there is nothing new in this observation, it is however, interesting to observe the evolution of story tellers that are weaving tales in 21st Century popular culture.

In 1917, Max Weber introduced modernity as the cause for the “disenchantment of the world”. He held the view that the traditional world was being eroded by the ‘modern’ processes of rationalization, secularization and bureaucratization. What we lost as a result were magic, the spiritual and animistic – as sense of the supernatural. The implications of this were that:

‘…. Principally there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play, but rather that one can, in principle, master all things by calculation. This means that the world is disenchanted’.

Stuart Hall defined the resulting modern society as:

‘Modern societies are therefore by definition societies of constant, rapid, and permanent change. This is the principal distinction between “traditional” and “modern” societies. Modernity, by contrast, is not only defined as the experience of living with rapid, extensive, and continuous change, but is a highly reflexive form of life ….’.

The changes in how we perceive the world were substantial. Gregory Smit observes that this shift in thinking was:

‘The unprecedented transformations of the modern age are an indication that ideas have consequences. Ancient traditions were left behind in favour of a world that we projected for ourselves as the product of conscious human choice. Freedom, emancipation, liberation and self-determination became the watch-words of the age’

Discussion Overview

There are two parts to this discussion, if you wish to navigate:

- A discussion of what is driving the modern secularisation of storytelling

- An analysis of the secularisation of the supernatural from films and TV

Part 1: PoMo the Clown

It’s somewhat disconcerting that many academics that write about postmodernism start off with the caveat that postmodernism is next to impossible to define. It’s this type of ephemeral dialectic that has left it as a signifier of the arcane; the near ultimate trump card of the journey-man philosopher.

Postmodernism is the cause to the symptom I want to talk about. So, I’ll briefly discuss this in a cultural context. Part of the conceptual trouble is that the term post-modern suggests a chronology. However, Theodor Adorno correctly observed that ‘Modernity is a qualitative, not a chronological category’. To this point, Matei Călinescu makes the interesting suggestion that modernism and postmodernism can be occurring at the same time, “The clash between the two modernities’:

“Two conflicting and interdependent modernities – one socially progressive, rationalistic, competitive, technological; the other culturally critical and self-critical, bent on demystifying the basic values of the first.”

Without getting too side-tracked, it is the effect of postmodernism on culture that I want to focus on. How postmodern story telling is different from the (pre)modernist traditions. The effect of this shift in thinking has been defined by Jean-François Lyotard as postmodern society being characterized by the disappearance of the ‘grand narratives’ or ‘metanarratives’ of modernism, such as Marxism or the belief in the Enlightenment project of linear progress. These grand narratives are replaced by ‘language games’ that involve linguistic and symbolic production. This thought is developed to a sharp point by Terry Eagleton:

‘We are now in the process of wakening from the nightmare of modernity, with its manipulative reason and fetish of the totality, into the laid-back pluralism of the post-modern, that heterogeneous range of lifestyles and language games which as renounced the nostalgic urge to totalize and legitimate itself’.

David Harvey observed that postmodernity privileges heterogeneity; the result of this is a discourse which is increasingly characterised by fragmentation and indeterminacy. Leaving many with the shortcut that if it is confusing, it must be postmodern then?

The Emerging Secular Frame

If culture has been reorientated to challenging the ‘metanarratives’, one of the most prominent targets is that of religion. This role of secularity in modern society has been investigated through a vibrant debate of secularisation-theory:

Secularization theory has claimed that most or all forms of religion are in the process of vanishing from the world and are being replaced by secular institutions, beliefs, and subjects

Frank Lechner has detailed the implications of this thinking:

Where once a sense of the sacred marked the landscape itself, where social order used to be visibly embedded in sacred order, architectural relics attest to a profound change: the vanishing of the supernatural from the affairs of the world, the waning power of religion to shape society at large. In landscapes and architecture, secularization has become visible.

Secularization also describes the world the West has gained. In this world, culture is marked by pluralism: religious faith takes many forms, and meaning has many nonreligious sources.

Even when they make their way into popular culture, supernatural notions thereby lose any sacred aura. In this world citizenship requires no religious attachment, and society sets no rules for religious conformity. Secular events shape the rhythm of public life; publicly significant religious occasions tend to lose their transcendent content.

This ‘demystification of all spheres of life’ is the symptom of what Max Weber was observing in 1917, of the “disenchantment of the world”.

Secularization as a theoretical basis has been challenged and some have tried to increase its relevance by making its application more contextual. Alternatively, by clarifying ‘secularization is most productively understood not as declining religion, but as the declining scope of religious authority’. Another explanation is that ‘secularization’ is marked by the decline in individual religious practice’. The impact of this change in context away from the individual, is defined by Luckmann,

“The more the traces of a sacred cosmos are eliminated from the ‘secular’ norms, the weaker is the plausibility of the global claim of religious norms”

When we think of how we experience the spiritual today, there is also the nature of disambiguating between religion and spirituality. Paul Heelas makes the point that:

‘With secularization theory very much dwelling on the decline of religious tradition in “Western” settings, the challenge is to develop alternative explanations—explanations that specifically attend to the growth of New Age spiritualties of life’

He cites the growth of a range of contemporary spiritual practices from Yoga to Reiki, but cautions that ‘ Compared to the “real thing”—religious tradition—New Age spiritualties of life are impoverished, vague, attenuated, and quasi-spiritual, if not secular’. He makes the point that while there is frequent discussion of church attendance being in decline, other spiritualties of life are growing. There even appears a preference to be ‘spiritual’ over being religious – that being less structured speaks to the key themes of freedom in postmodern identity.

Even in a postmodern experience, the consistency of human imagination and spirituality suggests that this is something deeply connected to our collective psychology. Jonathon Haidt, in his influential work on Positive-Psychology, ‘The Happiness Hypothesis’, discusses ‘Divinity with or without God’, identifying sacredness and a spiritual side of psychology as being necessary for happiness.

Dis-enchanting Story Telling

If we come back to the issue of ‘disenchantment’, Michael Saler, from a sociological perspective, has defined the impact of modernity:

‘In its broadest terms, maintains that wonders and marvels have been demystified by science, spirituality has been supplanted by secularism, spontaneity has been replaced by bureaucratization, and the imagination has been subordinated to instrumental reason’.

Daston and Park are stronger on this point as active rejection of the ‘marvelous’ for a longer period of time:

‘Central to the new, secular meaning of enlightenment as a state of mind and a way of life was the rejection of the marvelous’

The secular drive can be illustrated by a recent loose-quote by Richard Dawkins, evolutionary biologist and a proactive secular thinker:

‘I think it’s rather pernicious to inculcate into a child a view of the world which includes supernaturalism’

More moderately, Claire Chambers makes the valid observation that it’s not as simple as prohibition:

‘Stories are crucial to culture and shouldn’t be prohibited but nor should they be installed as secularist totems, as some New Atheist writers try to do. It’s perfectly possible to be sceptical of magic while still believing in the enchantment of stories.’

The Supernatural and Fantastic in Popular Culture

When we look at film and TV today, there is a rich canvas of science fiction and fantasy. It is possible to counter the premise of this discussion, that we are more enamoured with the marvellous and enchantment as our executional ability almost matching our most vivid creative imaginations. In the postmodern world Jean Baudrillard, has made the observation to this point that the sense of real and unreal becomes tenuous – reality collapses into hyper reality. One of the implications of the post-modernistic interpretations of culture is the fragmentation and merging of ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture into a form of ‘aesthetic popularism’.

‘Stories may not actually breathe, but they can animate… Stories animate human life; that is their work. Stories work with people, for people, and always stories work on people, affecting what people are able to see as real, as possible, and as worth doing or best avoided’. Arthur Frank

Many of the supernatural tales that we are exposed to today originate form a melange of different literary and oral sources. Frank Zipes makes the point that story telling started when were first able to speak and socially communicated stories were the vehicle.

It’s useful to briefly review the role of fairy and supernatural tales that rub Richard Dawkins the wrong way. Frank Zipes illustrates that many story types: religious, patriotic, fairy tales all have more in common than differences. The exception being that fairy tales tend to be secular and are not based on a prescriptive belief system or religious codes. Fairy tales started in 1500’s as brief, secular narratives that were new in expression. Interestingly, these stories tend to incorporate poor protagonists that, in the face of trials, demonstrate the character of royal heroes. Bruno Bettelheim, makes that observation that many start with the ‘hero’ being subjugated by antagonists that think little of him and his/her abilities. They also tend to be very urban in settings. Zipes makes the observation that the fairy tale hero is often a seamstress or tailor ‘who has numerous adventures and encounters with the supernatural in pursuit of a ‘new world’ where he will be able to develop and enjoy his talents”. As an aside, it’s interesting that Harvey Cox, in the Secular City, linked secularisation with the process of urbanisation. Fairy tales often present a juxtaposition of the secular and supernatural. It is a function of stories and myths to provide us with a vehicle to overcome contradictions in society and culture.

Fairy tales are often employed by postmodern writers, as is defined by Lisa Fiander:

‘One is always tempted to identify a postmodernist impulse in a writer’s borrowing from fairy tales, whatever the writer’s nationality; the shiftiness of those narratives and their association with folktales—an older, oral form of storytelling— makes them attractive to fiction writers interested in exploring postmodern challenges to realism’

This ‘borrowing’ from older stories and genres is an observation also made by Lyotard in discussing science fiction, that:

‘…postmodern nostalgia tends to downplay the critical tendency of science fiction, preferring instead to make the recycling of older texts in the genre as the crucial a feature of the genre as any. In a cultural climate of pervasive nostalgia, it becomes difficult to separate science fiction’s critical capacity from other similarly unreal genres- science fiction, particularly on television, becomes a set of familiar tropes rather than the practice of extrapolation and cognitive estrangement from the real world’.

Part 2: Taking the super out of supernatural tales

In the last few years there has been a tendency within science fiction for writers to find a secular and mundane explanation for many of the traditional supernatural tales. Many of these tales started off as folklore and fairy tales and have become cultural phenomenon in their own right. This appears to be mirroring a postmodern attitude on the secular or mundane explanation for the supernatural. I’m not suggesting that all supernatural stories are being demystified or disenchanted on mass; the dominance of the Harry Potter franchise is proof of this (however, the very Muggle-ness of Harry’s childhood speaks to this tension of worlds). Every week Hollywood appears to produce a new TV series that involves some millennial war between Vampires, Werewolves and other magic denizens. However, it is possible to identify a new subgenre of the mundane supernatural.

Since it’s a supernatural number, I’ll limit my observations to 10 examples, however, there are many more.

1. Secularised: Zombies

The most obvious example here is the current Zombie mania

Here the Voodoo and occult origins of the zombie, withand their supernatural role originating from the enigmatic Baron Samedi, Loa and Lord of the Crossroads. In the modern frame, the secular explanation of zombies is contagion by a virus. Like many other postmodern stories, it is often man that is the cause of the viral contagion.

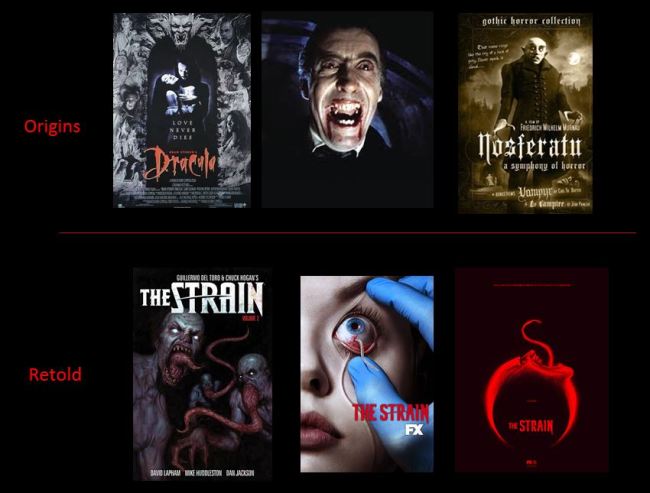

2. Secularised: Dracula and Vampires

Likewise, the new TV series ‘The Strain’ explains vampires as a form of parasitic infection. This is very different from the unholy origins that Bram Stoker imagined from the original. While many of the plot elements remain similar, Chuck Hogan and Guillermo Del Toro’s approach re-imagines the reality of the vampire through a more scientific lens.

3. Secularised: Frankenstein

Frankenstein, as the ‘modern Prometheus’, is a story warning of many of the themes of modernity that have been discussed above.

Victor Frankenstein seeks to mirror the power of God in creating Adam from death – a very supernatural theme. Prometheus in Greek myth is punished for stealing fire from the heavens; so Dr Frankenstein is punished for stealing the life force or ‘lighting’. What we tend to find in modern versions of this story is the same plot of losing control of his creations, either in the science or technology needed to create these other sentient lives. The abuse of technology by man is constant through all of these stories.

4. Secularised: The Mummy

The mummy is a tricky supernatural tale to look for parallels to, since it’s specific to Egypt. The attempts in the Mummy Movie trilogy, to extend the Egyptian curse origins to China were lacklustre.

However, at a plot level, the idea of an advanced race with a founding culture, monumental architecture and suspended in a ‘sarcophagus’ was central to Ridley Scott’s Prometheus as an origins story for his Alien Quadrilogy. There are several ‘mummy’s’ in this one film amongst the humans and the aliens if you think through how they travel (not wanting to totally destroy the plot).

5. Secularised: Ghosts

Ghost stories remain a perennial favourite, especially after Hollywood found a ready source of plots in Japanese cinema.

The more secular versions of ‘ghost in the machine’ tend to be about human consciousness transferred into a computer, so that the individual lives on in the digital computer world.

6. Secularised: Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

As with Frankenstein, this supernatural tale draws on the impact of when it was first written. I have written extensively about this theme as a ‘Doppelganger’ story in an earlier post.

What we tend to see in new versions of this story is a psychological explanation for Mr Hyde. Originally it was a ‘magic potion’ that unlocked the supernatural bestial, Mr Hyde. Modern versions of these stories are inversions, where the face of evil is hidden within – the psychological face of sociopaths, psychopaths and sadists.

7. Secularised: Gods

There is an increasing trend to demystify the gods of mythology.

Perhaps the show that has pushed this boundary more than most is Stargate. It started with the premise that Egyptian Gods were really technologically advanced parasitic-aliens. Then it introduced explanations for other gods in our culture, such as the Asgard, who look like many alien ‘grey men’ that are recounted in abductee stories. The Stargate series ends with a cosmic battle between a new race of omnipotent beings that have transcended our plane of reality but have ultimate power here. Their almost godlike powers are presented as being beyond known mythology.

More recently, a different telling of Asgard has been brought to the big screen by Marvel through the Avengers and Thor franchises. Here the blend of technology as magic is deliberately self-aware. In Thor, the characters Erik Selvig and Janes Foster discuss this:

Erik Selvig: I’m talking about science, not magic.

Jane Foster: Well, “magic’s just science we don’t understand yet.” Arthur C. Clarke.

Erik Selvig: Who wrote science-fiction.

Jane Foster: A precursor to science fact!

In the Avengers, the nature of divine nature is addressed more directly, postmodern style:

Natasha Romanoff: These guys come from legend. They’re basically gods.

Steve Rogers: There’s only one God, ma’am, and I’m pretty sure he doesn’t dress like that.

[Captain America leaps out of the Quinjet]

8. Secularised: Supernatural Plagues

If the Gods exist, then their wrath is manifest on the world.

The Biblical plagues as the wrath of God are the motivations to the plot of many films with religious story lines. In the mundane versions, we see the same global implications wrought by humans on themselves through losing control of modernity. They usually revolve around variations on ‘flood’ narratives – natural events that are ‘extinction level’ events.

9. Secularised: The Ordained Knight

In medieval times, stories accustomed us to the knight winning a magical sword, with which, to fight the evil of a community. These swords came from magical beings such as the ‘Lady in the Lake’ or were blessed by religions.

We are still telling stories that ‘god’ endorses our hero’s; these are demigods that live in both worlds. Greek gods live as half-humans or half-Olympians; King Arthur lives on Avalon the mystical isle.

In modern storytelling, we don’t get bequeathed magical weapons, we ‘engineer’ them. Iron man, as the archetypal ‘tin man’ is a human construction. Batman’s powers are written in opposition to Superman’s powers, in that he trains himself to preternatural skills and augments these with technological.

10. Secularised: The Monarch

The tenth of these secular versions of the supernatural needs a bit of introduction since we have become distanced from these thoughts by the process of modernisation. One of the advantages in the pre-modern age was that as a ruler, you controlled history. There was collusion between the secular and religious castes to affect a belief that God had ordained a particular families coronation. This was more common in Roman and Egyptian times, where ancestry to a god was a common claim by the core aristocracy. We see a similar pattern of endorsed monarchy in Judeo-Christian times, with many aristocratic families being able to demonstrate impressive religious endorsement. If you are religious, it’s hard to argue with your ruler if God has endorsed their rule.

Previously, deities bestowed their gifts and favour on individuals so they could rule. House of Cards, throws this literally on its head (and its logo). Frank Underwood is Machiavelli-on-steroids; he is secular to the bone living without apparent morality. Every action he takes is through the manipulation of his human skills.

The mysterious end

Michael Saler suggests in this area that:

‘Fictions become one importance source, and mass culture, as the dominant purveyor of fictions, has become a locus of enchantment equal to that of modern science. (The emergence of “science fiction” as a distinct genre in the twentieth century is emblematic of the importance of these two areas for modern enchantment.)Western elites long defined mass culture and its enchantments as inherently irrational, fit only for the childlike hoi polloi, but historians have demonstrated that elites themselves participated in mass culture because it offered enchantments that appealed to their reason as well as their imagination.

Most of us have friends and associates that could be called either high and low-cultural resource individuals. It’s a generalisation, but most of the high have indulgent vices in the low; also, that many in the low admire and find aspects of high culture aspirational…just inaccessible. Most people appear to enjoy a sense of the supernatural even if the enchantments are only a momentary suspended disbelief.

This discussion has attempted to bite off a lot of popular culture and explore the secularisation of supernatural storytelling within a postmodern frame. This has been though an analysis of current thinking on the implications of postmodern thinking and also what secularisation means within this context.

To illustrate this thinking, ten examples of where mundane explanations for supernatural themes have been uses in recent film and TV storytelling have been used as examples where the drivers behind postmodernism are present:

- Zombies

- Dracula and Vampires

- Frankenstein

- The Mummy

- Ghosts

- Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

- God

- Supernatural Plagues

- The Ordained Knight

- The Monarch

Of course this sub-genre is likely to continue, perhaps a version of Rumpelstiltskin who uses a ground breaking 3D printer or Rapunzel being a victim of hypertrichosis.

That we are seeking to define and understand the universe in more mundane and secular ways is evident, the question is, what do we lose? What is wrong with a bit of mystery, if we don’t project an author onto its presence? Is the issue that we are driven to want answers too much? A world without the mystery that the supernatural brings feels a big monotone, the other meaning to the word mundane is not secular but boring. Taking the super out makes the supernatural natural and familiar.

To some questions there are no answers, to some answers there are no questions

Buddha.

Recent Comments