June

13

June

13

Tags

Opening a Window to the Future [Part 2]

Why are we so negative about the future?: Future Part 2

“The future is like a dead wall or a thick mist hiding all objects from our view’

William Hazlitt, 1822

Cultural Metaphors of the Future

One of the manifestations of the authenticity trend in society today is the cherry-picking what parts of past we want to celebrate. This trend borrows frequently from our pre-modern past to address concerns of today. This selective-revisionism finds elements that address concerns of today, e.g. the current craft or artisan movement is a story we want to hear in response to the fears of large mass-producing factories. Thinking about solutions from our past is easier than thinking about what will happen next – what does the future hold for us?

A hypothesis to help us explore this block of looking into the future, is that we are constrained by the metaphors we use to understand different epochs of time and our own identities.

There are three questions that the future raises in terms of how we perceive ourselves in the future. Since our minds are story telling in nature – we create “a human narrative of the self” .

“Narrative construction begins with making sense of the world, organizing the space in which we exist, comprehending the events that unfold around us. These are minimal narratives, stories we tell ourselves about where we are and what is happening around us, connecting representations of segments, temporally in the case of space, causally in the case of events” (Tversky 2004)

Story telling involves being able to credibly and engagingly create and share an entire world (the diegesis of a narrative). To accomplish this, the author has to establish key intersections of time and space. Psychologically, in our own personal stories, we are protagonists – the leading actor. To understand how we perceive the future, it’s informative to look at how the metaphors that we use and how these influence our perceptions about the future and who we are.

A ‘“Metaphor is a tool so ordinary that we use it unconsciously and automatically… it is irreplaceable: metaphor allows us to understand ourselves and our world in ways that no other modes of thought can.” (Lakoff and Turner 1989: xi).

So as automatically as we can consciously use metaphors as tools to comprehend the world, they can also be unconsciously used to frame how we think, without us realising we’re using them. To mangle a metaphor: the tail can wag the dog.

Who are we? In an earlier blog, I looked at the profound influence a person’s name can have subconsciously on what they do in their life, through theories of nominative determinalism and name-letter effect. If we are looking at time-and-space, it’s interesting to look at how we contextualise our surnames – as family names – in our language and minds. You need to know where you come from before you can move forward. As Terry Pratchett warns:

“If you do not know where you come from, then you don’t know where you are, and if you don’t know where you are, then you don’t know where you’re going. And if you don’t know where you’re going, you’re probably going wrong.”

To get to a metaphor that does influence how we look at the future, I want to take a slightly oblique path exploring identity and the past. Parallel to this topic, I have long been interested in the incongruence, of many people that profess to be evolutionists, calling themselves descendants of family members. If modern societies are secular and evolutionary, why are terms of reference not about evolutionary progress in language? I’m an ascendant.

Without wanting to drift too far off topic, Claude Lévi-Strauss was able to demonstrate that kin-systems are structural subconscious metaphors for how we perceive and organise the wider world . To perceive one’s self as a descendant runs counter to being an evolutionary ascendant. At first glance, this might appear to be mere semantics and dialing up the magnification too much; however, the respective meanings of: antecedent, ancestor, ancestry all look to a previous progenitor. They all mean ‘a person from whom one is descended’. Even ascendant suggests the tracing from an earlier generation – it doesn’t quite suggest the improvement or advance upon.

The word descendant came into the English language in the 14th Century from the French decendre, from the Latin ‘to climb down’. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) in their formative work on cognitive metaphors were able to identify different classes of metaphors, one of the main groups were orientation-metaphors. This has been further elaborated upon by Theodore Brown:

“Orientation metaphors that are strongly cultural in content form an internally consistent set with those that emerge most directly from our physical experience. The up-down orientation metaphor can apply to situations that contain both physical and cultural elements, such as

He’s one of the higher-ranking officials in the agency.

These people have very high standards.

I tried to raise the level of the discussion.

Whether the experience on which an orientation metaphor is based is directly emergent physical experience or one drawn from the social domain, the core metaphorical framework is the same in all of them. There is only one verticality concept ‘up.’ We apply it differently, depending on the kind of experience on which we base the metaphor.”

In a very semiotic function, positive metaphors have an opposite. The same is with orientation metaphors: ‘Upward orientation tends to go together with positive evaluation, while downward orientation with a negative one.” (Zoltán Kövecses, 2010). Up is good, down is bad. It is worth noting that there are height and depth metaphors that work here, since orientation is three-dimensional, with depth suggesting degrees of intensity. If we look at examples in this context of ‘down’, ‘decline’ or ‘decent’ we can see many parallels with the conversation on dystopias compared to heavily eden-esque utopias.

It’s not a new observation that western cultures are a consumerist society, what impacts on this consuming- behaviour is core to many people’s immediate concerns and fears. We can find the use of the orientation-metaphor widely in the social-narratives of the post-GFC Western societies today: ‘the market is down’, ‘in crisis’, ‘flat’, ‘needs to turn around’, etc. However, just the idea of a decline as a metaphor rather than up does not appear to explain the cultural-pervasiveness of the dystopian genre. Yes, up is good and down is bad. What are the terms of reference? There appears to be some additional meaning at work.

“Don’t’ walk into the future looking backwards” – Dr Toy (Stevanne Auerbach)

In a world of increasingly fragmented meaning, who are we? If we think through the language of how we identify ourselves: individually and socially, people will often look to their names, family and countries for identity markers. This is why language that surrounds being someone’s descendants is informative. A descendant suggests a diminishment of a line, that we are somehow smaller than our ancestors. This is also something that is subconsciously used in language and represents the depth aspect of the orientation-metaphor. This is not something that is implicit in the meaning of genealogical words, but we do find it as a visual metaphor.

Visual Metaphors

One of the most common symbols here is the family tree. If we look at how they are illustrated, we can see something interesting. The progenitors are visually larger than life and subsequent generations are diminished.

What we see is a diminishing from the ‘founders’ even though the tree is ascending. If you do a websearch, the vast majority of ‘genealogy’ is visually presented as a descending tree from a shared ‘founder’. They illustrate the roots more than the branches. This is especially when presented as a text-based dendrogram; again illustrating this diminishing metaphor.

Think about what these two charts of the same canine genealogy suggest:

Part of this is the convention of decline comes from the influence of religion. While there are many differences in how the ‘people-of-the-book’ interpret the Bible, all think of themselves as the descendants of Adam. In particular, the ‘Fall of Man’ is another decent metaphor that takes us from Utopia in Eden. From this religious perspective, we are all trying to lift ourselves back to Eden.

This metaphor of the decline-of-man is pervasive in the bible and other examples can be found. What is interesting is that the same diminishment-metaphor can be found in other areas. In Christian traditions there is the concept of virtue which is the direct line back to Jesus as is illustrated in many different media, of the link back to God of the ordained. Connection to god is hierarchical and diffused.

Another example of this diminishment in Christian practice is discussed by Umberto Eco (1988), who suggested that the early Irish church was active in the pursuit to ‘rediscover or re-invent a pre-Babelistic language’. The idea that before the fall of the Tower of Babel that language had been closer to God and the languages that followed are fragments of this. ‘The Precepts Of Poets’ was an early Irish text Eco (1998: 20), explains that ‘the fundamental idea of this treatise is that in order to adapt the Latin grammatical model to Irish one must imitate the structures of the Tower of Babel’. The precepts describe the 72 wise men of the school of Fenius Forrsaid who planned the reconstruction of the pre-Babel language. Eco suggests that this movement was inspired by Isaiah 66:18 ‘ I shall come, that I will gather all nations and tongues’.

If we look to idioms in today’s language, we talk about ‘a chip off the old block’ (from Theocritus) , and when we are great thinkers we are uncharacteristically humble and ‘we stand on the shoulders of giants’ , rather than we are ‘giants on the shoulders of smaller men’.

The Golden Age

This employment of diminishing-metaphor can be found as a constant and more complex and influential leitmotif in Greek and Roman beliefs. Ovid (Metamorphoses 1.89–150) introduced the idea of the Ages of Man being expressed in the hierarchy of gold, silver, bronze and iron age. These were different eras that illustrate the movement from a perfect age through to a more corrupted era. This is the metaphor of decaying from a golden age to lesser era of man.

This thought was captured by Tomas Cole his ‘The Course of Empire’ Paintings (1801–48), this was an allegoric warning for the young USA:

- The Savage State

- The Pastoral State

- The Consummation of Empire

- Destruction

- Desolation

But this is also more accessible in popular truisms such as: ‘The first generation in family makes money (goes from rags to riches); the second generation holds or keeps the money; and the third generation squanders or loses the money (and so goes back to rags)’.

This conception of the Golden Age has been very influential. Other than the Olympics we can see the influence of Gold to Bronze as a hierarchy – reinforcing that Gold was desired. . In popular culture, we talk to of the Golden Age of Hollywood ; also: Radio, Television, Aviation, Sailing, etc. It’s also formed how authors have structured their narratives, e.g. It’s the way that George Lucas explained the Rise of the Sith and the republic and the decay of the Golden Age. As Obi-Wan says to Luke in Episode IV introducing the light saber ‘Not as clumsy or random as a blaster; an elegant weapon for a more civilized age.’ The same theme is present in Tolkien, as humankind was the Fourth Age in his universe often contrasted with the more impressive Elfish achievements . There are the three great ages of modern comics:

The Age we live in

The implication is that not being in the Golden age is not being in Utopia.

The idea of diminishment from better times is one that is embedded in modern culture; at a time of global hardship and GFC, what are we meant to think? Down is bad, we are not living in a utopia. We use language to describe more glamorous times as being Golden.

‘The longing to be primitive is a disease of culture – George Santayana 1926

At its most simple, we appear to struggle with the future. Historically, we can easily fantastise about Eden-like situations that fulfil our Utopia dreams. The recent desire for sea-changes, down-scaling, etc. are all situations where modern life appears to present the solution of stepping outside of the rat race to join a form of perceived utopia. This does feel like an echo of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s thinking on the influence of society on ‘natural man’.

In popular culture, utopias are often defined by their dystopias. If you think about HG Wells’ the Time Machine, this illustrates the two sides of utopia. At the end of time, there is the pure side and the ‘wilder’ caveman side of human nature, even if evolved. This is also a theme of the TV series ‘Lost’ and ‘Lord of Flies’ By William Golding, where there is a descent into a more primitive state of humanity at times.

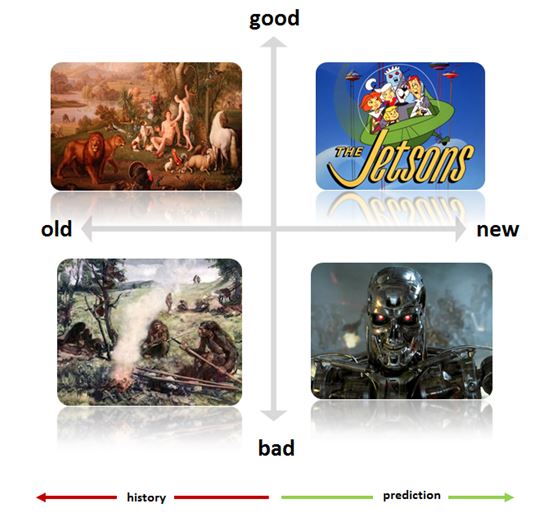

We can try to simplify how we relate to the past and future as typical storytelling.

When we look into the future, science fiction can only take us so far. We can make positive utopias such as the ‘Jetsons’ but this doesn’t help us to explore our humanity against the dystopia we believe we are living in today. This leaves us open to stories that stretch the dystopian themes of our real-world concerns: environment, politics, social forces, surveillance, disease, environment, outer-space, et al. As Gorden et, al have suggested, these stories are getting increasing ‘real’ as culture spreads up, but also in how films are capable of creating reality in WYSIWYG CGI.

This type of analysis suggests that a subtext to the modern condition is a belief that we are lesser than the generations before us. That we are not as great as previous generations; we are more egalitarian and democratic but at the same time more average. It’s easy to pick up biographies such as the Founding of the USA and read of a collection of men whose standards don’t appear to be around anymore. This was a more common theme in the 19th Century, in the 1840’s Thomas Carlyle created the ‘Great Man Theory’: “The history of the world is but the biography of great men”. In this version of the world, heroes shape history through their personal attributes and abilities and divine inspiration. This theory had a counter-point in Herbert Spencer, who argued that heroes are the products of their societies. This was thought the Nietzsche expressed in his conception of the Übermensch, or as we know from Siegal and Schuster above, Superman. This is the idea that someone’s innate abilities make them a superior-man. We know from mythology ) that humankind has a fascination with stories that centre of heroes. In a more postmodern world, where many of the grand narratives have been challenged, information and opportunity have been democratised, it’s harder to see singular Heroes step forward or if they genuinely are they are often hidden in the sheer volume of information out there.

The cliché of the 15 minutes of fame has been surpassed by a few seconds of glory in a tweeting-frenzy. Since we are a hero-centric story telling people, the lack of these prominent heroes has been replaced to some extent with a ‘celebrity-culture’ where we question these role-models, even if we vicariously engage with the glamour of their ‘lives’. Increased communication and interactivity, takes away from some of the glamour of any person in the spotlight. In this world of constant personal re-invention, it’s easier to feel lesser to the giants of the 19th and 20th Century. Perhaps our current fascination with dystopias is a transformative cultural catharsis to work through our anxieties.

Some have started to think of a collective response, Edward Wilson suggests:

“Humanity has consumed or transformed enough of earth’s irreplaceable resources to be in better shape than ever before. We are smart enough and now, one hopes, well informed enough to achieve self-understanding as a unified species . . . We will be wise to look on ourselves as a species ”

From a mythic and individual perspective, Joseph Campbell advised:

“We’re in a freefall into future. We don’t know where we’re going. Things are changing so fast, and always when you’re going through a long tunnel, anxiety comes along. And all you have to do to transform your hell into a paradise is to turn your fall into a voluntary act. It’s a very interesting shift of perspective and that’s all it is… joyful participation in the sorrows and everything changes.”

Perhaps, if all else fails, we trust in the wisdom of the Old Philosophers. Ovid, who with Hesoid, created the concept of the different ages of man, suggests that when the orders, Gold, Silver, Bronze, Iron and Heroic are completed ‘”Then they come back again in reversed order …” (Ovid. Metamorphose.15.249).’

So if our fears are technological, we can also wait to

Reblogged this on :: Culture Decanted ::.

Reblogged this on Going Box By Box and commented:

A fascinating post about why we think the past is so great.